A 20-minute long haul. Strap in for:

- Squirrels!

- Cybernetics!

- A man with a beard!

- Neoliberalism!

- TTLY: Old posts.

The fundamental law of accountability: the extent to which you are able to change a decision is precisely the extent to which you can be held accountable for it, and vice versa.

Dan Davies, The Unaccountability Machine, p.17

The Unaccountability Machine’ lies on a threshold that’s difficult for me to describe. I know it’s non-fiction, I know there’s a central narrative that drives it, and I’ve left it knowing more about the managerial world than when I first started reading it. But it also feels like a reference work, something you keep nearby and return to a couple pages every now and then to clarify some facts.1

I’m not even scratching the surface with that paragraph2 – my softcover edition is unscathed, sans the general wear and tear of reading. What you also get out of these three hundred pages is a (very) brief history of mid-to-late 20th century economics, as well as a crash course in cybernetics, a discipline that, with development, could have brought our world onto a different path. Still could.

I could give my Dad this book, tell him it’s a book on management, and he’d enjoy it. I think it might take him a while to understand what this ‘cybernet’ is – that it’s not all on t’internet – but, honestly, it wouldn’t be a bad first parse. People who misunderstand cybernetics have done far worse, like plant defective microchips in people’s brains, or start coups.

The Unaccountability Machine is one of those books you look up from and find the proverbial Candlestick of Understood Ideas is far from fizzled out. A slow burn; I’m not bright enough to fully take in the last three hundred pages, but hey, that’s what the re-read is for. Re-reads, and writing about them.

In his Preface, Davies sets up a few observations that his chosen anecdotes will later symbolise3:

- When someone designs a decision-making system of any kind, they simplify the world down to a model containing only what they consider to be essential details. Think how a map abstracts away all the detail of your street;

- We make models of the world because they make it easier to communicate with others when building the system – whether we’re aware of what harms may be caused by a model’s missing details, or not. Missing details are an unavoidable byproduct of models.

Systems make decisions. You input some sort of feedback – a button press, a lever pull, a wheel turn, a letter in an inbox, a prodding index finger against a rulebook – the system takes action on that feedback, as it was designed to do, and then you get an output. Knowing this, what Davies sets out to answer is the question we all have when we interact with systems, only for them to politely tell us “no”: who’s responsible?

For the British psyche, that question’s not the most important, but it is adjacent to our vital urges: to hound demands towards a member of staff4, twisting our Ts and and spraying our Ps a little harder each time we don’t get what we feel we’re entitled to.

Not too long ago, I went into an airport lounge to check in with the family. We quickly became audience to a lady in front, who repeatedly asked the reception staff where her wheelchair-using husband’s disabled access was, as they were due to fly soon.

Now, AFAIK, the only responsibility that that receptionist would’ve had was to phone up whoever was responsible for the care those passengers were entitled to. They got it, in the end… but supposing they didn’t? Well, the receptionist would then take on the role of a human face on an amorphous system’s body, and held responsible for a decision that they ultimately don’t have the power to change. (Pay no attention to the cosmic horror standing in plain sight.)

All the receptionist can do is follow protocol and phone the relevant authority up the chain of command, unable to guarantee that Something Will Be Done. Any feedback the couple could give, then and there, wouldn’t make their disabled access materialise faster.

I know, it’s a fairly innocuous example, one that miiight tango with the likes of Times colmunists who blame A&E waiting times on malingering youth, and red tape, all in the same breath. But I think what I experienced was a real example of the ‘accountability sinks’ that Davies describes in the book.

When a system causes tragedy to strike – when said tragedy could’ve been avoided – people always want to find someone to blame. That’s just yin and yang, isn’t it? When a crime’s committed, there’s a criminal behind it. Right?

But in many cases, blame is a comforting fantasy against disturbing reality. When we’re talking about systems, they don’t make mistakes, only the things they were designed to do. Sometimes, systems with accountability sinks make decisions that have no real owner, with horrifying results.

Because who in their right fucking mind would willingly put 440 squirrels into an industrial shredder?

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/airline-killed-440-squirrels-in-giant-shredder-1087522.html

In 1999, a shipment of red squirrels from Beijing made a stop at Schipol Airport, in the Netherlands, en route to a collector in Greece. However, they weren’t cleared with the right documentation – it wasn’t possible to send them back on a return flight, either. Euthanasia, per the laws designed by the Dutch Department of Agriculture, was the only option. To comply with this, KLM Airlines had invested in what is loosely described as the most humane option: a shredder.

Now, if you were the person who knew they were going to see squirrel puree on the inside of their eyelids, maybe you’d speak up. Maybe you’d say no. You know it’s wrong as hell, and you’re not gonna take it.

If your life up to that point was a story illustrated by Quentin Blake, pretty soon there might be medals involved. Maybe Queen Beatrix would outlaw poultry shredders and invite you to have tea. But, as you’ll remember, we’re not dealing with individuals in this story, we’re dealing with systems.

No-one was responsible: but as Davies points out, a law that states “document your imported animals properly or they will die” is a model of the world that lacks safeguards. It assumes all good-hearted people can be trusted to inform relevant institutions of the imported animals in their care, on threat of violence; surely no-one is careless or lazy enough to doom Foamy to the shredder.

The second fallacious assumption I already touched on, tongue-in-cheek: that anyone, tasked with euthanising an animal, who believes the interpretation of the law to be unethical, would refuse:

It is neither psychologically plausible nor managerially realistic to expect someone to follow order 99% of the time, and then suddenly act independently on the hundredth instance.

Sure, when it’s you, it’s easy to imagine yourself as a Stanislav Petrov:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1983_Soviet_nuclear_false_alarm_incident

It’s easy to forget that, in real life, these acts of defiance are million-to-one events – in context, it goes against all the rational reasoning the job expects of you. Yes, maybe they crop up nine times of ten; we also tacitly agree that tomorrow will continue no worse than today, so long as we all stick to the rules.

You couldn’t have found the Platonic ideal of a renegade employee, who defies commands that put lives at risk, even if you tried. That was not the purpose of the system. The very act of shredding 440 squirrels tells all: the system’s purpose was to produce subordinates who respect and obey the power that managers have over them. 999 times out of 1000, that is how big things get done.

Therein lies the trouble: when a system accepts a decision it hasn’t been designed to handle – i.e., an exception – then, unless that system isn’t force-stopped, it will produce unintended behaviour – the sorts of things that models do not anticipate.

‘Unintended and unanticipated’ can be funny if it’s corrupting the instructions of a video game:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OvNDcVRlyYk

Not so for shredding squirrels, obviously.

The last place anyone in a managerial role wants to be, then, is within a system where they, personally, have to decide what actions to take. If it was an individual person who’d decided ‘fuck them squirrels,’ the fallout at Schipol would have them crack like an egg under a hydraulic press.

As cathartic as it might feel to blame a disaster on one person, or a group of people, accountability sinks create an infinite loop, where the power to change a decision, and thus be held proportionally accountable, is always offloaded to someone else:

https://bsky.app/profile/tiffanycli.bsky.social/post/3lu234mq5322o

More importantly – you might’ve already figured this out – accountability sinks insure that, even when a decision taken by a business is judged as unethical, careless, capricious, etc., it is following policy. No matter how much feedback we give by way of public backlash, there is nowhere within the system – the business – that our input may be fed in to produce an output that affects the material world.

Accountability sinks are one reason why trans patients have to jump through so many hoops, and wait so long to see a doctor for gender-affirming care – and that’s just the first appointment:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v1eWIshUzr8

For a brief moment, though, there was a promise of a different future, where all this wasn’t the case – where people did have the power to veto decisions and update policy in real time.

Stafford Beer5 didn’t invent cybernetics, but he pioneered its use in management. He collaborated with the Chilean government6 in the 1970s to create Cybersyn, the world’s first semi-automated planned economy.

At this point, however, I feel I should further touch on what I mean by the word, ‘system.’

Although I’ve been using ‘system’ as a noun, in the context of cybernetics, ‘system’ can also be an adjective. If I say ‘banana,’ for most of you, that’s a noun that means, ‘the yellow elongated berries produced by flowering plants in the genus Musa7.’ No trouble there, I imagine.

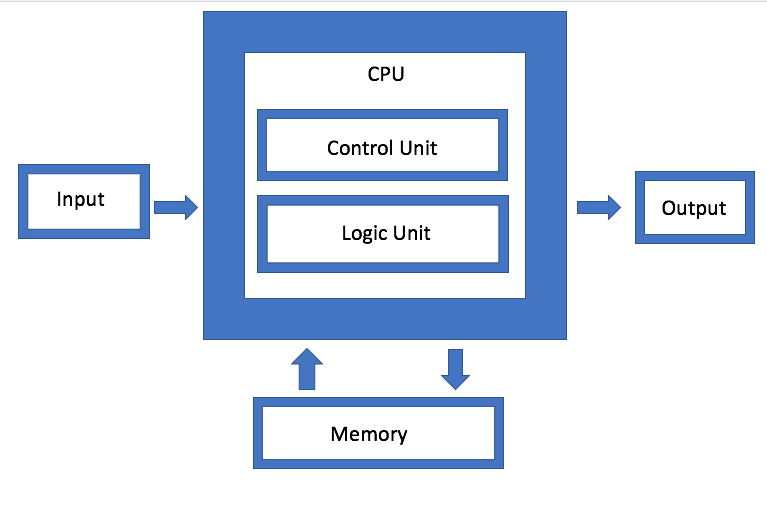

As for ‘systems’ – perhaps your mind’s eye conjures some lump of plastic that contains precious metals and silicon chips. Cyberneticians are primarily concerned with what information flows through a system, and how it’s controlled. The von Neumann diagram describes a system:

Your computer or game console fits this description. And so does this computer built in Minecraft:

But as examples of systems go, it’s better to start with something simple, with clear causes and effects explainable in 300 characters or less. Take one of Davies’ examples – a thermostat.

To human bodies, the ambient temperature of a room ranges between two states: ‘too hot’ and ‘too cold.’ Our heating ranges between ‘off’ and ‘full blast.’ We can regulate the room’s ambient temperature by turning a dial, which takes our human input and produces an output.

The number of states a system can be in is defined by its designer (me). Cyberneticians call this ‘variety.’ Just as temperature increases or decreases, a dial can only be turned clockwise or anticlockwise. Cyberneticians call this the ‘principle of requisite variety:’

Anything that aims to be a ‘regulator’ of a system needs to have as much variety as that system.

You probably realise that dials can regulate a lot more systems than just temperature. If it’s a variable that can only ever increase or decrease between a defined range of numbers, a dial’ll do it:

If something can only ever be ‘ON’ or ‘OFF,’ no inbetween, there’s no better alternative than a switch – light switches, plug sockets, transistor gates, etc..

Most systems, however, are – to use a favourite phrase of my digital forensics tutor – ‘a bit more complicated than that.’ The raw, unadulterated human is a system that quite famously introduces a lot of variety that’s hard to reduce. Hence, the need for managers.

Managers can’t make humans fit perfectly into the principle of requisite variety. But hats off to them – they do try.

Now, about Cybersyn.

Cybersyn was supposed to be a compromise between capitalism and communism’s modes of production. You know those feedback terminals at airports that show you they’re listening very carefully to the problems that persist, year in, year out? What if they did something? What if the workers had the power to directly report the state of affairs to a command centre, where civil servants would allocate resources in real time?

That, in broad strokes, was Cybersyn. A video essay by Plastic Pills gives the quick rundown:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJLA2_Ho7X0&t=17m29s

By letting workers manage their resources, labour, and production locally, and report directly to a control centre via telex, Cybersyn avoided the bottlenecks of ‘massive government bureaucracy.’ At the same time, however, those who operate the control centre are directly responsible for acting upon the data they receive. There’s accountability.

Workers aren’t monoliths, they’re a plurality, and so, not everyone was on board with this sort of automation. For a brief two years, however, it boosted Chile’s economy. Until it didn’t. Planned economies are capital-C Communism, according to the 1970s US government. When it bankrolled a coup on the Chilean government, Cybersyn was led out on a leash.

In common parlance, to ‘automate’ something means to make an existing task faster, more efficient. In part, this might be due to simpler problems that cybernetics could solve – like transistors, and how to make them smaller, and how to build a computer. The complex solutions to social problems were ones that cybernetics could map out, but they took much longer.

We’ve taken this meaning for granted. For example, when the 1960s rolled around, and electronic computers became affordable for businesses:

There might have been an opportunity to rethink the basis of financial reporting […] but there was no incentive to do so […] What actually happened was that most companies commissioned an electronic version of the same bookkeeping processes.

To Stafford Beer, this was akin to reviving the world’s greatest geniuses, and asking them to memorise the phone book to save turning pages. In other words, the variety of information processed by companies didn’t change with the advent of computers, when it absolutely could’ve.

This is odd. It’s become even more odd over the last forty years or so. It’s as if many companies’ day-to-day operations have no real vision for the future – just more everything forever. Oh, a spokesperson can gesture at plans to do this, or that, but what’s the system’s plan for getting there? How does it know it’s on track?

And it gets spooky: if a company’s got no clear vision of the future, then, when its products take lives, it’s not uncommon for it to find an accountability sink not within its own system, but in entities that exist outside of it, who are given no power to enact change.

Like the public. Gareth Dennis recently covered a case of killer Brightline trains in Florida on his Railnatter podcast:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H-AK0fmhhoI&t=24m24s

If a section of a rail line consistently kills pedestrians and motorists at level crossings, that is its purpose. This requires a real-world, material change on Brightline’s behalf. Signs won’t cut it, because the information a sign transmits assumes pedestrians are in a state to receive that information and adapt according to it.

Brightline argued that pedestrians are to blame. But pedestrians are black boxes (a metaphor to describe any system whose processes we have no knowledge of). You can’t possibly know what state they’re in, and, as Dennis says, it is physically impossible for the human body to sense these trains coming until it’s too late.

It is very tempting to imagine One Very Stupid Pedestrian who got killed on the back of their own stupidity, but in this case, there are no grounds whatsoever to nominate them for a Darwin Award. Two of Beer’s most well-known aphorisms argue that we should be thinking in the exact opposite way:

It is not necessary to enter the black box to understand the nature of the function it performs.

Stafford Beer, The Heart of Enterprise, p. 40

And, of course, “the purpose of a system is what it does:”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_purpose_of_a_system_is_what_it_does

From our pedestrian POV, a rail line and the operators running it are also black boxes. We are not in the black box, we don’t need to open it to know the system’s not working, and, being outside, we’re in no position to change it.

But here’s what we do know: fences exist. Bridges exist. It’s terrible urban planning to have two vastly different forms of traffic intersect. The better solution would be to border off the tracks, or to raise them out of the way of pedestrians and motorists. That’s nigh-on common sense. But nooooooo, common sense would cost money.

‘Caveat emptor’ is a cruel accountability sink, but when it is policy to blame people with no power over you, to implore us to imagine One Very Stupid Pedestrian, then how else can you describe it?

It’s a world of absurd trolley problems out there:

https://neal.fun/absurd-trolley-problems

Perhaps the most absurd of all: why don’t the railway operators put fences up to make it harder for moustache-twirling villains to tie people to the tracks?

(Answer: because the purpose of a system is what it does. And an accountability sink that fools a regulatory body, but not members of the public.)

So, what happens when technology is used in ways that not only automates parts of an activity, but empowers the workers doing it? We know Cybersyn was built to answer this question, but, really, it wasn’t online long enough for anyone to learn from it. Instead, Chile got a front-row seat to the birth8 of the neoliberal revolution, a world where giving workers power to plan the economy is, quite literally, unthinkable.

Neoliberal philosophy conditions us to think of ourselves as individuals; society’s just a big chain of individual transactions, nothing more. It asserts, as a ground truth, that all humans are driven by a selfish desire to maximise the benefits of transactions, whilst minimising cost. There’s no such thing as businesses under neoliberal thought – just a set of individuals who interact with each other.

Because of neoliberalism’s emphasis on individuals, I think it’s a sticky mode of thought to break free from if you’ve not been raised to think otherwise. An apt quote from Small Gods that I found the other day:

“Slave is an Ephebian word. In Om we have no word for slave,” said Vorbis. “So I understand,” said the Tyrant. “I imagine that fish have no word for water.”9

If you treat individuals as a sum total, and not part of a greater whole, it neuters much of your ability to understand and talk about systemic power. Cory Doctorow offers an analogy:

If you offer me a payday loan with a ten heptillion percent APR and I accept it, that’s voluntary, it’s the market, and there’s absolutely no reason for anyone to pass comment on the fact that 100% of the people who take those loans are poor and 100% of the people who originate them are rich.

https://pluralistic.net/2025/07/19/systemic/

‘Power,’ as I understand it now, is the extent to which decisions affect the actions of others, uncountable, who are not involved in the decision-making – now, and in the future.

Doctorow often deploys a ‘centaur and reverse-centaur’ analogy to explain the power relation between workers, bosses, and AI. Cybersyn was a sort of artificial intelligence, in the literal sense: people made it up. It turned workers into centaurs, reporting information at a superhuman rate. It wasn’t designed to replace workers, but to empower them.

This is not the impact of AI on workers today. At many companies, the future of work seems to be this: one full-time employee (the CEO), and thousands of temporary contractors hired to fix all the mistakes made by the software that replaced them.

Or, if you work as an Amazon courier, or on warehouse floor, you’re already living in the World of Tomorrow. You are the reverse-centaur, monitored by AI, down to the eyeballs. You’re not empowered, but controlled:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/08/02/despotism-on-demand/

As a writer, I accept that there is a future where AI might empower me to write better stories, but it ain’t this one. I don’t feel empowered. I’m a minor nameless character in a novel where every oligarch believes he’s the One True Author and self-insert protagonist: I am forced to fit someone else’s mould; can never be trusted to command a project; and can be killed off in a single line should they so choose.

We should be bringing conversations about power to the dinner table. Power, and systems. As a start, the next time you hear Facebook in the news, think not of Mark Zuckerberg, or legions of moderators, web devs, PR staff, or even The Algorithm, but its own organism10.

Neoliberalism or no neoliberalism, businesses have always been, in one way or another, a form of artificial intelligence (‘artifice’ being the operative root) – Charlie Stross explores this in a 2017 talk, ‘Dude, you broke the future!’:

https://www.antipope.org/charlie/blog-static/2018/01/dude-you-broke-the-future.html

[Corporations are] clearly artificial, but legally they’re people. They have goals, and operate in pursuit of these goals. And they have a natural life cycle.

All these AI hucksters who hype up ‘artificial general intelligence’ and at the same time are terrified of it churning the planet into grey goo or paperclips? Their companies are already doing that.

Tesla is a battery maximizer—an electric car is a battery with wheels and seats. SpaceX is an orbital payload maximizer, driving down the cost of space launches in order to encourage more sales for the service it provides. Solar City is a photovoltaic panel maximizer. And so on.

Paris Marx did a four-part podcast series on data centres and AI – whatever you think of the technology, it’s clear the purpose of OpenAI, et al., is to terraform the planet to build data centres:

https://techwontsave.us/data-vampires

They’re energy maximisers, and they’ve been let in like a vampire, but fuck knows where the heart is. Not that it matters: a drop of blood’s all a vampire needs to get back on its feet11.

I’ve nattered on long enough. Suffice to say, The Unaccountability Machine is an amazing book that’ll have you seeing cybernetic problems everywhere once you’re done. For what is this book, if not a system of knowledge – and what is the purpose of a book, if not to influence the way we view the world?

What is the purpose of knowledge, if not to empower? That is what it does.

- Which, at a glance, describes pretty much any work of art you want to take inspiration from while working on a project. ↩︎

- I mean, I could’ve said it was like a dictionary, only it’s one that you read cover-to-cover, but that’s an analogy going in the wrong direction. ↩︎

- Something that we in the literary trade might call rhyming action:

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mqrarchive/act2080.0035.004/59:22?page=root;size=100;view=text ↩︎ - Politely. ↩︎

- As a person, Eden Medina described him on an episode of Tech Won’t Save Us as ‘a cross between Orson Welles and Socrates:’

https://techwontsave.us/episode/61_project_cybersyn_shows_all_tech_is_political_w_eden_medina

Look at a photo of him, and tell it to me straight – tell me he didn’t wander into this world from out of Discworld’s L-Space.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Stafford+Beer&title=Special%3AMediaSearch&type=image

This man is Ridcully in the flesh.

↩︎ - And because Davies brought it up – I have to point out that, prior to this, Beer collaborated back and forth with Friedrich Hayek, one of the ‘founding fathers,’ as it were, of neoliberal economics.

That’s the thing about cybernetics: it’s a transdisciplinary field. It’s not bound to any ideology in particular; rather, it’s a vessel that ideology can fill.

I can’t say where Beer was politically, post-coup. What can be said, however, is this: a man who chums with neoliberals one day, and finds himself in their way the next, can’t help but think. And Stafford Beer did enough thinking for five men combined. ↩︎ - No idea where I read this, but apparently it’s also the largest herb in the world. ↩︎

- One piece of imagery that I’ve seen repeated a lot is Cybersyn as a symbol of an unborn future. Pinochet’s coup ‘aborted’ it. I think it’s more akin to shark fetuses: one future ate the other before it had a chance to develop. ↩︎

- The academic turn of phrase for this is ‘hermeneutical injustice’ (supposedly, although I think it’s to do with academics being turned into hermits because no-one is allowed to have fun in public places anymore). ↩︎

- In a world of Gormenghasts, every Big Tech baron believes he’s Steerpike, and that he, alone, steers his world towards a future of his design. He can move fast and burn down the library, if he likes – but the rules and rituals of the castle were set in perpetual motion long ago. It exhales hot air in its data centres, yearns for the tantalizing taste of hard water (not that deionised muck), shits sensitive data, and (presumably) flushes it somewhere to be forgotten. Steerpike or no Steerpike, the Gormenghasts of the world shuffle on; the most these ‘great men’ will ever do, really, is crawl through the bowels, and watch. And when the final shitstorm washes the rest of us away, hide. ↩︎

- But what sort of vampire would settle for just a drop? That’s the real question… ↩︎

TTLY… (permalink)

- [Jun 14] Liminal Time https://brologue.net/2024/06/14/the-liminal-is-the-means-by-which-all-is-revealed/

- [Jun 20] The Pen Shall Make Ye Fret https://brologue.net/2024/06/20/i-just-make-stuff-up/

- [Jun 21] WTDWA? – An Essay For My St. Andrews Uni Application https://brologue.net/2024/06/21/wtdwa/

- [Jun 23] ANSWER ME THESE FALSE POSITIVES THREE https://brologue.net/2024/06/23/when-you-get-what-you-want-you-dont-want-what-you-get/

- [Jun 30] The Flat Tyre https://brologue.net/2024/06/30/the-flat-tyre/

- [Jul 7] Parachuting and Fully-Automated Luxury Politicians https://brologue.net/2024/07/07/dont-forget-to-bring-the-long-fall-boots/

- [Jul 10] You Are Peter Shorts (Review) https://brologue.net/2024/07/10/judge-me-by-my-shorts-do-you/

- [Jul 18] When the Science in Your Storytelling is Sus https://brologue.net/2024/07/18/author-author-theres-an-evopsych-in-my-book/