- Tier lists: What they are (and aren’t). More or less…

- How to Smash With Statistics: What’re those ‘official’ tier lists all about, anyway?

This Brologue is for folks who have a tendency to read too much into tier lists.

I dislike tierlists, and I can’t get enough of them. They’ve been the lifeblood of eSports discussion seemingly since forever. At your local, it’s probably the topic de jour, et demain, et demain, et demain.

A: “My character loses to X.”

B: “Are you crazy?”

A: “Well, my character’s top five, X players are carried, and I don’t care. What does your character do about X?”

B: “Get hit.”

A: “Right. Because your character’s huge. Mine isn’t!”

It is astonishing how much information folks try to cram into a single image. Tier lists attempt something that’s seemingly impossible: Organise the game’s roster into a ranked hierarchy. The higher the character places, the ‘stronger’ they are, i.e. their attributes give them a better edge over the competition on average.

Put another way – given two imaginary players of equal strength, determine the viability of each character to win games. This is the basis for all tier lists, as well as matchup charts, which are really just tier lists focusing on how a character fairs against the rest of the roster. Usually, matchups that go either way are +0, or even; positive matchups (where the subject character wins) are +1 or more, negative -1 or less. From here on, when you read ‘tier list,’ keep these in mind.

Tier lists aren’t like a race where the person who crosses the finish line first is objectively the winner. They are like races in that everyone and anyone who wants to get to the finish first participates, and they think they know a shortcut.

Tier lists are, at their most fundamental, a complex, symbolic human behaviour – the sort of thing we’d call ‘culture.’ It’s like wearing a kilt to a Scottish wedding. You can’t play any new competitive game these days without running into someone’s opinion that looks like this:

Tier lists are so embedded in platfighter culture that they really merit further inquiry. What I’m about to say is a sweeping generalisation, and it’s based on my own experiences (and thus my own prejudices). When we discuss the competitive aspect of these games we play, it’s usually not without reference to concepts rooted in sports psychology, economics, and, usually, when there are discussions on character bans (looking at you, Steve), politics gets thrown in as well.

Take frame data. Any discussion that has to do with how fast a character can perform any given action, or recover from any given action, is an economical matter, and one that we usually tend to discuss in a vacuum. Given an action, and a given situation, we obviously want to know how we can get the most bang for our buck. It’s not totally unlike going into a shop and reading the labels on similar products that read “£X/100g.” Of course we want to maximise utility.

Frame data, assuming frame-perfect inputs, is absolute in a vacuum. Once you add humans into the mix, it’s a bit more complicated. I myself am guilty of perpetuating a certain myth about reaction time in ‘The Art of Olimar’s Down Air.’ It may be true (in Smash Ultimate) that 18 frames (1/3 of a second) is the minimum, but people rarely, if ever, react to a specific move if they’re not already anticipating it. Roll out the gorilla suit1:

There’s no end to the number of VODs online where someone has managed to reset their opponent, tried to read where they’re going to move, and ended up punching the air. We talk of frame data in a vacuum, knowing that even the most consistent players are not ‘frame-perfect,’ and yet in many a discussion we pretend we’re frame-perfect every time anyways. But I digress.

How to Smash With Statistics

We try to wrap tier lists up in objective-looking spectacle, and some of us (myself included) understandably interpret them as solid fact. Let’s face it – all tier lists are subjective readings. This is not to suggest that “tier lists don’t matter.” Those words are perhaps four of the most insidious in our vernacular (I’m guilty of uttering them myself). Of course they matter.

This might sound silly, but I, like many others, know the feeling – that the more you see the same top characters appearing in everyone’s tier lists, the more you start to believe it, even if those characters don’t have any players in your region. It’s an odd tautology. You start wondering why you’d pick any other character. What is it about disclaimers of subjectivity that fails to prevent us from thinking objectively?

In economics, there’s this model that continues to be spread called homo economicus. Basically, to simplify things (as all models do), economists assume that every human action is driven by a desire to maximise benefits, and minimise risk, effort, resource expenditure, and so on. “Give a lazy person a hard task, and they’ll find the easiest way of doing it,” sort of thing.

You almost start to believe that homo economicus is inevitable, like they’re some cosmic force of the Universe that has been foreordained. But you can’t run physics on economics. Besides which, homo economicus isn’t real. There are few domains in life where people think or make decisions as homo economicus would. Making tier lists appears as one such domain.

But humans are not cold, calculating, utility-maximising machines – if we were, we wouldn’t make such a fuss about tier lists in the way that we do. There is so much beyond the game than just picking the horse who we think is most likely to win.

Tier lists reveal something about human thought that’s often taken for granted – it’s dialogical, even if you’re alone. When we’re trying to organise the roster into tiers – a problem-solving task – we almost inevitably imagine ourselves debating with, or explaining our thoughts to, some ‘other’ entity, even if that entity does not exist in our reality.

Programmers employ the same dialogical patterns when trying to figure out coding problems they can’t solve yet. They call it ‘rubber duck debugging:’

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubber_duck_debugging

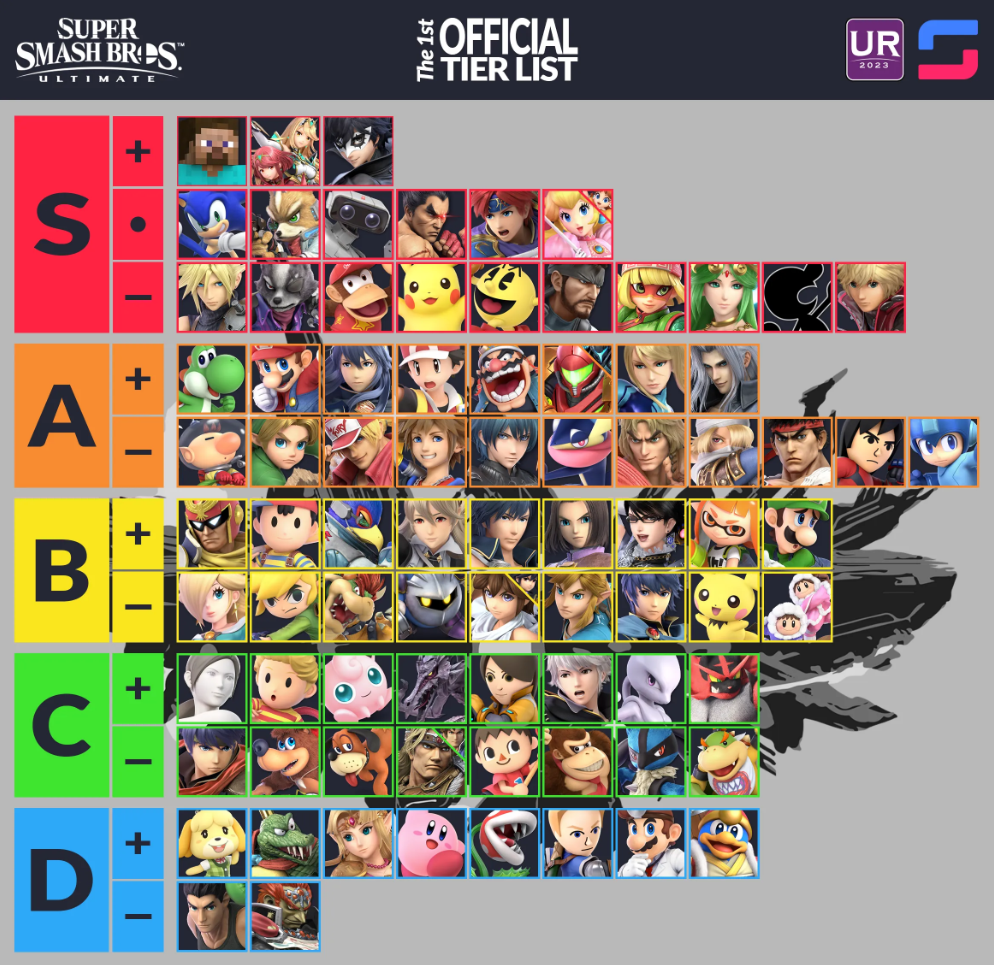

But what about when a game has aged enough to start getting ‘official’ tierlists – say, the one published by BarnardsLoop last year?

Does this image divine some objective truths about the Ultimate metagame? Is Pikachu really busted? Can a skilled Ganon really beat any Steve? We ought to take a look at the methodology:

Any player within the top 101 on any of six global rankings covering a majority of 2022 were eligible to be part of the panel for the tier list: UltRank 2022, OrionRank 2022, EchoRank 2022, ΩRank 2022, 1000Rank 2022, and RaccRank 2022. Out of a total of 155 eligible players, ballots were filled out by 71. Panelists were asked to rate each character they formed an opinion on from 1–10, with 10 being highest and 1 being lowest. They were also asked to provide an ordered top 5 characters in the game… Tiers were then determined via K-Means Clustering.

https://blog.start.gg/ultranks-first-official-ssbu-tier-list-4a35bf3dcfc3

In short: This tier list is an aggregation of opinions among the top 101 players on six different power rankings, who were asked for their opinion. Not every character received the same level of evaluation:

Steve was the only character to be evaluated by every panelist, while Mii Swordfighter was evaluated by the fewest, with only 65 panelists weighing in on them.

https://blog.start.gg/ultranks-first-official-ssbu-tier-list-4a35bf3dcfc3

This is how statistics work. You start with qualitative user stories, devise a way of quantifying those stories, mapping them to a model (which itself is sometimes based on subjective numbers!), and then put painstaking effort into making sure the visualisation you show to others doesn’t tell a pack of lies. More or less…

Here’s another example to drive the point home. Remember when that guy who dressed up as Wario bought Twitter? And it seemed as though your TL was filled with people jumping ship to Mastodon? A group of researchers did the numbers to evaluate these posts as drivers of social influence, and their findings are summarised in this post:

Without statistics, we couldn’t verify that these posts were what made it so easy to switch in small, tight-knit communities – nor would we have the knowledge to explain why Mastodon saw significant dips in its userbase, before steadily bouncing back, in what Cory Doctorow describes as ‘scalloped growth:’

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/11/of-course-mastodon-lost-users/

All someone’s tier list really tells you is “I think these characters are broken, these ones are fine, these ones are bad.” Even the official Ultimate tier list is an aggregation of top player opinions. And that’s all they should say. This isn’t a debate on whether we should value the qualitative or quantitative elements over each other. We need both.

Statistics get a bad rap, and don’t get me wrong, it’s not without reason:

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Statistics#Statistics_and_evil

At the same time, this is not a call to be cynical in our scepticism. Darrell Huff’s “How to Lie With Statistics” was intended to stoke a skepticism in how statistics can fool us, and, in true schismogenesis fashion, it ended up making generations of people fear statistics even more, as a kind of formless trickster who you must always trust, but verify. Tim Harford sums it up in this blog post:

https://timharford.com/2022/01/how-to-truth-with-statistics/

His book, ‘The Data Detective,’ is a kind of antidote to the aftermath of Huff’s book. Even if you’re not a maths buff (I’m not!), it really is worth the read:

https://timharford.com/books/datadetective/

There genuinely are some games where the disparity of character balance is self-evident. Big glowering elephant in the room: Super Smash Bros. Brawl. I struggle to imagine the timeline where a skilled Brawl Ganon can beat any Meta Knight. You’re trying to beat a character who gets to play the game at all times with a character who, if he dares to express himself, gets pelted with hitboxes and dies. No postmodern, structuralist who-doo will get me out of that one.

Tier lists matter, then they don’t matter; they don’t matter, then they do. How do we stand apart from this? We’d like to give others the courtesy of listening to their opinions, but it’s such a draining discussion – once someone tells you that X character is mid-tier, you can’t just delete that from your mind. You may find yourself debating, to no-one in particular: “Well, are they?”

For the record: I don’t care who you are, nor who you play, you’re as entitled to complain as I am. Let’s not prevaricate around the bush: we complain about a lot of silly things in these games of ours. The last thing a tier list should do is to vindicate someone’s prejudices for who gets to complain about something, how much, and how often.

There’s one genre of games where tier lists are a guilty pleasure of mine: roguelikes. I like listening to videos from other Binding of Isaac players who wax lyrical about items that are really, really good. Those kinds of videos get my imagination whizzing about item combos that aren’t immediately obvious. If you play Isaac, you’ve had those kinds of runs – one item’s effect cascades into another, and another, and through pure serendipity, you’ve turned into an unstoppable killing machine.

Those tier lists are fun. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m away to watch a few more…

- I was put onto this idea by Molk, a GnW player, and Lattie, one of the labbers in the Bowser Discord. Honestly, I think they make a great point: I get a lot further trying to watch my opponent’s movements rather than the moves themselves. ↩︎