OoOoOoOoOo your genes determine that you will read to the end to learn about OoOoOoOoOo:

- Oh, it’s THIS guy again: Hey, I’ve seen this one… or so the Monomyth tells me.

- A Story of Science-telling: Criti-hyping evolutionary psychology (without the criticism) to explain storytelling;

- My God, Pure Paleoideology: What were we doing until 12,000 years ago? Was it all just evolution?

- On balance: Surprisingly, authors know what they’re doing. We should hear what they have to say.

I. Literature’s Cryptid: The Monomyth (link)

The first warning sign came in the introduction, where the name ‘Joseph Campbell’ stared me dead in the face, glassy-eyed, unwashed gutter-breath sputtering a theory that refuses to stay dead. As Spencer McDaniel writes, The Hero’s Journey may be a vox pop method of storytelling, but it’s no Monomyth:

https://talesoftimesforgotten.com/2020/12/31/the-heros-journey-is-nonsense/

The Monomyth theory is far too blurry to claim any historical provenance. That’s why it’s nonsense. It promises to be a theory of everything for literature, yet when stood against the historical record, it’s no more a crack at making the Philosopher’s Stone; a minority of clichés that, today, could be found on TV Tropes with a thousand non-exhaustive sub-articles. Interpreting stories with it involves more shifting goalposts to get them to fit than it’s worth.

And yet, for it to be “thoroughly entrenched in high school English literature classes all over the English-speaking world,” surely it’s not all nonsense? Fantasy writer Brandon Sanderson, for example, cites it in this creative writing lecture:

It’s more accurate to say that the Hero’s Journey is a product of the last half-century, urged into relevance from the writers of Star Wars, who found the myth of the Monomyth to be, based on their own experiences, ‘true enough.’ The problem with this is that once you start judging literature only through what stories have in common, you grow cynical of the idea that literature builds upon itself.

As Rachael Lefler of Owlcation writes: “Why bother reading both the Aenid AND Watership Down if they’re essentially the same book?”

https://owlcation.com/humanities/How-Monomyth-Theories-Get-It-Wrong-About-Fiction

I am not immune to the Monomyth. My Mum’s read a lot of romance novels and thrillers in her time, from authors such as ‘Sunday Times Best-Seller,’ and I’ve found myself thinking, time and again, “What’s the point if they’re the same book with the same plot?” Who am I to judge?

https://brologue.net/2023/11/05/fantasy-for-mums/

If I wanted to write a story that Mum would read, following the Monomyth would be worse than useless. Lefler argues that literary connoisseurship is far more important to aspiring writers. If you want to write a detective story, there’s no substitute for reading Raymond Chandler, Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle and G. K. Chesterton. If you want to write a story that stands out, that breaks new ground, you have to know whose shoulders you’re standing on first.

In the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook 2007 edition, the late Terry Pratchett argued we should take literary connoisseurship beyond our preferred genre:

There is a term that readers have been known to apply to fantasy that is sometimes an unquestioning echo of better work gone before, with a static society, conveniently ugly “bad” races, magic that works like electricity, and horses that work like cars. It’s EFP, or Extruded Fantasy Product. It can be recognized by the fact that you can’t tell it apart from all the other EFP.

Do not write it, and try not to read it. Read widely outside the genre. Read about the Old West (a fantasy in itself) or Georgian London or how Nelson’s navy was victualled or the history of alchemy or clock making or the mail coach system. Read with the mind-set of a carpenter looking at trees.

It’s not just about reading the classics. If you want to break ground with that no-nonsense detective story, you’re gonna have to read – gasp – fantasy! Sci-fi! Romance! Check into Eddie the Non-Fiction Kid’s library and check out with some real stories, capische? And if you know what’s good for you, learn a little history. Keep it real.

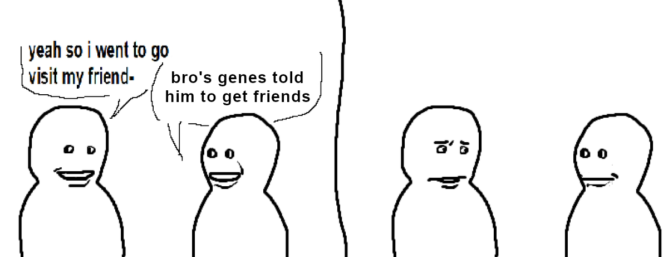

II. Bro’s Genes Told Him to Control (link)

No. That wasn’t the first warning. I’d ignored that one.

Will Storr’s The Science of Storytelling is an odd book. It’s not on my postgrad’s reading list. In fact, I was recommended this book by a Twitter post years ago. The premise seemed interesting enough, and I thought it relevant to tack on as extra material.

I don’t want to crank the lever and cry ‘SCIENCE BRO!’ as such, but if your book’s title has the word ‘science’ in it, then – and I did judge the book by its cover – its theses adopt the verisimilitude of having stood up to the scientific method. Which is why the first chapter is, more or less, underpinned by a criti-hype take on evolutionary psychology, a proposed subfield notorious for producing unfalsifiable just-so theories at a pace too rapid to be considered happenstance.

That was irony, by the way.

Evopsych (a.k.a ‘Darwinian psychology,’ ‘human sociobiology’ and ‘A Story of Science-Telling’) presents itself as something you can’t just casually unpick or disregard, like swiping past a video on social media you almost certainly know is full of bullshit. It’s a bundle of hypotheses about human cognition and behaviour that you can tell to your friends, family, and passersby on the street, and find them nodding in vague agreement. It sounds… truthy.

On the other hand, if you’ve heard anything about evopsych before, I’m 99% sure it’s not because of the actual ideas it posits (“we are products of evolution” isn’t a bad premise on the surface), but a certain audience those ideas attract. They’re the sort of folk who claim that natural selection alone can prove we are genetically wired (read: destined) to seek out criminality, hierarchy, war, or greed; believe that, and they can make you believe much worse.

Not unlike the Monomyth, starting with the TL;DR of Darwin’s theories is more open-ended than you’d think, and this means it lends itself to being fertilizer for shithead ideologues to make their means to an end palatable. Not all evopsych enthusiasts see themselves as bedfellows with eugenicists, nor successors to the phrenologists before them, but if you are a eugenicist, then evopsych is the perfect smokescreen, and you might as well call yourself one to confuse everyone else.1

III. My God, Pure Paleoideology (link)

The author seems keen to promote evopsych not as a third wheel to neuroscience and anthropology2, but as the main act:

Evolutionary theory tells us our purpose is to survive and reproduce. These are complex aims, not least reproduction, which, for humans, means manipulating what potential mates think of us. Convincing a member of the opposite sex that we’re a desirable mate is a challenge that requires a deep understanding of social concepts such as attraction, status, reputation and rituals of courting. Ultimately, then, we could say the mission of the brain is this: control.

Will Storr, The Science of Storytelling, pp. 16-17

Right off the bat, the evopsych framing is front and center. Evolution, alone, can explain why we behave the way we do, and thus, how plot elements work to stir our emotions.

He takes no pause to consider what this might imply. Were this actually the case, we could quite happily throw anthropology in its entirety out the window with few consequences; eschew the full, uncut archive of human experience and social/political experimentation, in favour of a few shelves, and say, “Well, it looks better this way, and it makes more sense.3” I find that quite myopic.

There’s a brief section in Chapter 3 of David Graeber and David Wengrow’s Dawn of Everything where they argue starting from a common evopsych claim: hierarchy-seeking behaviour after groups pass a certain number is an adaptation from our simian ancestors. Social inequality, therefore, is an effect of genetic destiny. Some erudite Pleistocene archaeologists, “forced to confront” recent evidence of royal burials and commons areas, propose no alternatives. Open and shut case, right?

The Davids bring in the work of Christopher Boehm, an evolutionary anthropologist and specialist in primate studies, who writes that yes, we inherited dominant and submissive behaviours from the simians we descended from, but what separates humans – and human societies – from other primates is that not only can we consciously choose not to act in a certain way, we also understand how our society is impacted if we do not act to keep bullies in check:

Carefully working through ethnographic accounts of existing egalitarian foraging bands in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia, Boehm identifies a whole panopoly of tactics collectively employed to bring would-be braggarts and bullies down to earth – ridicule, shame, shunning (and in the case of inveterate sociopaths, sometimes even outright assassination) – none of which have any parallel among other primates.

David Graeber & David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything, pp. 174-5

Emphasis my own here:

While gorillas do not mock each other for beating their chests, humans do so regularly. Even more strikingly, while the bullying behaviour might well be instinctual, counter-bullying is NOT: it’s a well-thought-out STATEGY, and forager societies who engage in it… understand what their society might look like if they did things differently…

Ibid.

Boehm argues this is the ‘essence’ of politics, and it’s not a 20th-century idea – the Davids trace it back to Artistotle’s description of humans as ‘political animals.’ Despite the evidence, however, Boehm still concludes that, until around 12,000 years ago, all human settlements that came and went followed the exact same egalitarian social arrangements. Suddenly, hierarchy! Talk about conservative4 cognitive dissonance.

So, according to Boehm, for about 200,000 years political animals all chose to live just one way; then, of course, they began to rush headlong into their chains, and ape-like dominance patterns re-emerged.

Ibid., pp.177

That’s Graeber’s trademark irony, by the way. Our genetic nature, Boehm writes, is hierarchy-seeking, yet our poiltical history is egalitarian. Boehm’s argument, even though it shrugs and says, “I dunno guys, I’m just spitballing here,” opens a plothole between the Middle Paleolithic and Neolithic Revolution that evolution can’t explain alone.

That our prehistoric ancestors were not as equally capable of organising themselves into different political structures beggars belief. That this was purely down to evolution, doubly so. If future anthropologists only have sparse archaeological evidence from the past 40 years to judge us, they’d be as absurd to claim we, and our ancestors, were hardwired to organise our economies based on capitalist principles.

But what about that threshold, the magic number that explains why everything went to shit when we started building cities? In Chapter 8, the Davids repeat that the conventional, “textbook” version of human history posits “our capacity to keep track of names and faces, [is] largely determined by the fact that we spent 95 per cent of our evolutionary history in tiny groups of at best a few dozen individuals.”

For hunter-gatherer societies, new and old, it goes like this: pair-bonded families (you, your siblings, and your parents) were the basic unit; they would form bands with five or six related families (your aunties, uncles, cousins) to hunt together; during rituals, bands would join with other bands to form bigger clans, but these were no larger than 150 members. This estimate is taken from comparing the size of our brain to other primates.

What evopsych claims here is that our best shot at total solidarity and efficient decision-making is with our closest blood relatives. Except when it’s not:

Many humans just don’t like their families very much… Many seem to find the prospect of living their entire lives surrounded by close relatives so unpleasant that they will travel very long distances just to get away from them.

Ibid., pp. 543-4

The Martu clans of Australia are often cited as living proof of the arrangements just described – yet, as far as quantitative data can be gathered for modern hunter-gatherer societies, natal kin make up less than 10% of their population. In other words, they are predominantly populated with metaphorical kin:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1199071

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S004724841830157X

As recent genomic research suggests, it’d be accurate to say the same of prehistoric hunter-gatherers:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aao1807

Another plothole yawns open. People who lived during the Upper Paleolithic were as capable of identifying themselves as being part of larger imaginary structures beyond their homes. They could imagine solidarity with countless people of whom a majority they would never meet, well before the first cities emerged.

This is a loose summary of Graeber and Wengrow’s counterpoints. I don’t pretend that they’re infallible, nor that I’ve got it right; they have taken the claims seriously, and explored them with a broad, transdisciplinary line of inquiry. If we’re to understand what makes stories tick, us writers would do well to follow that example.

I could go on. Fitting the evidence to evopsych, not unlike trying to fit stories to Campbell’s Monomyth, seems less of a scientific exercise, and more an ideological one. It is a part, and not the whole that is otherwise suggested.

IV. Balancing the Books (link)

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve found some genuine insight from the first chapter. When it’s not been flirting with evopsych, or uncritically name-dropping Campbell, and instead focusing on what writers through the ages have observed, it’s not bad. For example – using active voice to write prose is usually better than passive voice, because it orders actions and their participants accordingly, i.e.

“Jane kissed her Dad.”

Is a better narrative sequence than

“Dad was kissed by Jane.”

This is an observation that predates evopsych, and does not rely on its existence to be explained.

Overall, I would have preferred it if the author had began with an anthropological approach, even if he is not an expert in the field. He could bring in case studies from researchers outside of his community – for example, Indigenous people. A web search yielded the following thought-provoking article from Adrienne S. Chan:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv1v7zc0t.17?seq=4

Storr cites James Geary’s I is an Other and Benjamin K. Bergen’s Louder Than Words to establish that some neuroscientists consider metaphor “the fundamental way that brains understand abstract concepts, such as love, joy, society, and economy.” I think Chan’s experiences of metaphoric pedagogy – in her own life, and in her work with First Nations youth – would be an excellent followup:

Metaphors are ways of understanding social and educational contexts… when the “exiting language is not capable of adequately describing the topic term or the listener does not possess the necessary language to understand the topic term.5“

Adrienne S. Chan, Storytelling, Culture, and Indigenous Methodology

Storytelling is part of Indegenous methodology: “Stories hold within them knowledges while simultaneously signifying relationships. In oral tradition, stories can never be decontextualised from the teller.6“

We heard a cultural story of Coyote, a kind of trickster, enchanter, and magician, whose symbolism refers to an alchemic way of interpretation… By ‘alchemic,’ I mean to signify that knowledge is more than material: it is also about the spirit, mind, and heart, that combine to create something new.

Indigenous storytelling, in one way, uses metaphor to communicate understanding where language does not suffice. The stories, themselves, and the events that happen within them, are treated as an extended metaphor; after the speaker finishes the tale, they then enter an open dialogue with their listeners, where interlocutors discuss their interpretation of the story, and what they think the metaphors are trying to teach.

As these are the interpretations of a researcher, this could be balanced by direct accounts from First Nation Canadians, researchers and lay people, letting their voices be heard. One scholar Chan cites is Dr. Jo-ann Archibald, Q’um Q’um Xieem, though not the chapter she contributed to the 2018 anthology Memory, edited by Philippe Tortell, Mark Turin, and Margot Young.

Developing a storied memory means that a storyteller has to keep using memory, repeatedly telling the stories to others… the responsibility for learning traditional stories accurately and intimately is essential for those who become storytellers; it is part of an intergenerational pedagogy of learning.

Dr. Jo-ann Archibald, Q’um Q’um Xiemm, Memories, pp. 236-7

It’s these sorts of voices, and this added context, that, by way of counterpoint, would make Storr’s arguments much, much richer.

At this point, I’ve scratched the surface on something that bothered me, and I will definitely come back to this in future, but I think I’ve said all I can say for now.

I’m gonna bugger off back to my ebook. Here’s munecat:

- For example: This article from the July 16th 1993 edition of the Daily Mail, a UK newspaper hawkish for far-right policy and pretends its journalistic standards reflect “what everybody’s thinking:”

https://archive.is/86YSW

The headline reads “hope”, and the bottom line is, “It could soon be possible to predict whether a baby will be gay and give the mother the option of an abortion.” I don’t think I’m reading too deep into this by saying this sounds a lot like, “Wahey, let’s exterminate the gays!” Please elaborate what the problem is with having a child that might turn out to be gay. I’d love to know.

A story that keeps the nuance of studies is not mutually exclusive with a story that makes your eyes glaze over, but the Mail, suffice it to say, believes it can’t be done. Because it won’t – the framing of this article is consistent with the party line since Lord Rothermere took ownership in the 1920s:

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Daily_Mail#Viewpoints

The ‘gay gene’ palaver was a caricature of a study of genes that were speculated to have some small influence on male sexual orientation. This has failed to be replicated in future studies; until it has, the ‘gay gene’ argument fails the scientific method’s most fundamental epistemological test – that what you say can be proven with an experiment that can be repeated.

↩︎ - As in, his sources rooted in evopsych are in proximity to those in neuroscience and anthropology, but the former takes significant precedence in his points over the latter. ↩︎

- And yes, I DO know that I’m writing this only having read the first chapter. Let the irony come back to hit me if it turns out the whole book isn’t like this. ↩︎

- VERY small-c, mark you: “This is a brilliant and important argument – but, like so many authors, Boehm seems strangely reluctant to consider its full implications.” ↩︎

- Jensen, D. F. N. (2006). Metaphors as a bridge to understanding educational and social

contexts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 2–17. p. 9 ↩︎ - Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies. University of Toronto Press.

Kulis, S. S., Robbins, D. E., Baker, T. M., Denetsosie, S., & Deschine Parkhurst, N. A.p. 54 ↩︎