What an excellent day to read to the end and find such contemplative thoughts as:

- Liminal spaces – and why they feel comforting, yet eerie;

- Liminality in anthropology – and how it can explain said comforting eeriness;

- Persona 3 Reload, once more – and how the observing of its many rites of passage culminates in the most beautiful ending to a game I’ve ever played.

- (CW: THAT MEANS MASSIVE PERSONA 3 SPOILERS AHEAD)

Despite my best efforts to wedge myself between my bedroom’s walls, I cannot noclip out of reality and into the Backrooms.2 My current circumstances are, shall we say, betwixt and between one place and the next. I’m not in liminal space so much as I am in liminal time. Is there really a difference between the two?

Well, Wikipedia tells me that liminality is an anthropological subject:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liminality

This means the liminal space ‘aesthetic’ we’ve come to know over the past half-decade can be explored using anthropology, too. How couldn’t it be? At the core of every single liminal space image you will ever see is the visceral sensation of feeling misaligned in a setting that should be familiar. Making the strange familiar, and the familiar strange, is what anthropologists strive for.

Take schools. From a student’s point of view, we just sort of… know when school becomes a liminal space. During the day, you meet, talk to, and avoid so many people, your brain puts in a lot of work to filter most of it out to leave you with a fuzzy transmission. ‘Things’ and ‘stuff’ are happening – of that, you’re certain. Once everyone’s at home, though, what’s left is a shell – a ritual place, whose participants are mostly absent, and thus, devoid of purpose.

While I was studying at Abertay, students and faculty alike often remarked how maze-like the Kydd Building was. Every time you went in, it seemed as though one new area or another appeared from nowhere. I remember one evening I tagged along with the Programming Society’s committee to the student union’s storage, at the end of a dark corridor on the second floor. Where the corridor’s end once had two doors, a barricade temporarily condemned it to one. Cold, dark, empty – and freaky as hell.

Imagine a Where’s Wally? picture of a derelict shack, in the middle of nowhere, overgrown by motorways3. The only sign of life is a missing poster nailed to a telephone pole. If you squint, you can just about make out a sun-bleached Wally, reported missing… fifteen years ago. We keep trying to ward off the eerieness by filling in the blanks where people ought to be. Liminality feels so out-of-place precisely because the social structures that bind us, that feel like ‘the norm,’ have ceased.

What happens next can either be a moment that stretches out into infinity (at least until Death shows up); or, we move through that liminal space, and get to our destination. Either way, not unlike metamorphosis, liminal phenomena are what we pay attention to when transferring from one state to the next.

“If ritual-shaped, why no ritual? Make it make sense!” – and, indeed, we try. In Philip Larkin’s poem Church Going, the speaker ponders a time far from their present, where churches no longer house God – His kingdom, as with all things, dissolved into what Orson Welles described as ‘the universal ash:’

“Their parchment, plate, and pyx in locked cases,

Philip Larkin, “Church Going”, Stanza 3

And let the rest rent-free to rain and sheep.

Shall we avoid them as unlucky places?”

The transformation of place of ritual to unlucky, liminal space is quite blunt. Yet, in the very next stanza, the speaker is eager to speculate that churches will draw people anyway, retaining a purpose:

Or, after dark, will dubious women come

Philip Larkin, “Church Going”, Stanza 4

To make their children touch a particular stone

The speaker can’t help but contemplate the experience of its final visitors, before positing that no visitor could ever be final. The church may move through time, slowly drifting away from what it once was, but as long as there are humans who seek “a serious house on serious earth,” we will fill it with our serious selves, and we won’t know what’ll really become of the church until we get there. What the speaker experienced as the church’s identity, and where it will go, they don’t know.

Or, is it the other way around? Tale Foundry’s Talebot asks: what if liminal spaces want to fill themselves with us?

They were never meant to be lived in, yet it’s like they yearn for a final visitor to settle and become its new inhabitant. But the Backrooms is a special case: unlike the church, it’s obviously a one-way trip, and will never serve a purpose. The architecture is humanly possible, but an absence of life deprives it of all meaning. It’s got a heavy contrast to M. C. Escher’s Relativity – a structure that is physically impossible, yet is nonetheless home to a community of sentient beings.

![From Wikipedia: "[Relativity] depicts a world in which the normal laws of gravity do not apply. The architectural structure seems to be the centre of an idyllic community, with most of its inhabitants casually going about their ordinary business, such as dining. There are windows and doorways leading to park-like outdoor settings. All of the figures are dressed in identical attire and have featureless bulb-shaped heads."](https://brologue.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/relativity-1024x961.jpg)

In fictional settings like the Backrooms, maybe liminal spaces do want to eat us, to keep us as its prisoners and feed off our desire for meaning. Real life, however, is much more mundane. But that doesn’t make liminality any less interesting.

There’s a very simple framework we can use to better grasp liminality. John Walsh (a.k.a. Super Eyepatch Wolf), in a YouTube video titled, Horror in Impossible Places: Liminal Spaces and the Backrooms, summarises Victor W. Turner’s theory of liminality (and, in turn, Arnold van Gennep, who Turner built on):

The metaphors are apt – a hotel room connected to an elevator via corridor, a Venn diagram where ‘what was’ overlaps with ‘what will be,’ or Caterpie evolving into Butterfree through Metapod. The Caterpie/Butterfree metaphor, as a proxy, is useful for asking another question we might have about liminality: When Caterpie evolves into Metapod, at what point does it stop being Caterpie and become Metapod? No official Pokémon game has ever shown what they look like mid-evolution.4

We could claim there is a stable phase between Caterpie and Metapod – a ‘Caterpod’ or ‘Metapie’ – but defining a new phase doesn’t really answer the question. Evolution is something that just… happens, like a school being emptied of students and teachers. We’re not interested in the actual physical changes that Pokémon undergo, but that nebulous state between Caterpie and Metapod where it’s everything betwixt and between. It refuses to be reduced.

Turner’s work has also been observed by David Graeber in Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value. In his time studying the Ndembu people of Zambia and their rites of passage, Turner theorised that if the stages of a rite of passage are structural – say, a boy becoming a man, or a crown-elect forced to live as a commoner before becoming monarch – then passing through it, the liminal stage is its shadow, or the ‘anti-structure:’

Those who pass through it are at once sacred and polluting, creative and destructive, divine and monstrous, and ultimately beyond anything that can be explained by the order of normal life.

David Graeber, “Value as the Importance of Actions”, p. 21, https://davidgraeber.org/wp-content/uploads/2014-Value-as-the-importance-of-actions.pdf (Part of “Anthropological Theory of Value”)

Holly High, one of the authors of As If Already Free, a series of essays on Graeber, writes that liminality, in social contexts, is:

A kind of social limbo where one could glimpse all kinds of symbols, including the seeds of other ways of being… We will each pass through rites of passage whether we like it or not and whether we know it or not… If we can recognize a rite of passage for what it is, though, we do have some measure of freedom: a freedom to accept, or work with, or jam the symbols we live in these times of our lives.

Holly High, “As If Already Free: Anthropology and Activism After David Graeber”, Chapter 2: “Birthing Possibilities”, pp. 55-56

Liminal spaces, then, evoke both comfort and dread at the same time because they are suspended between two identities that cannot be reduced. They are spaces divided by zero – undefined, and with infinite transformative potential.

Talking of liminality, not talking about Persona 3 would be a missed opportunity equivalent to losing a winning lottery ticket in the wash:

https://brologue.net/2024/02/18/ludocrous/#i-never-felt-like-so-meow-meow-meow-meow

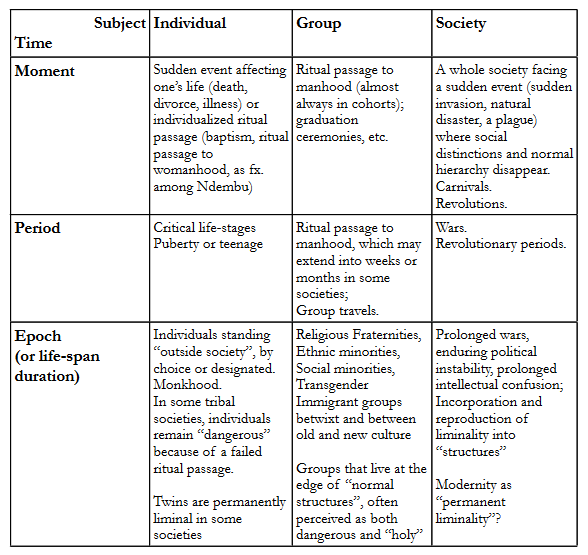

I’m no Junpei: Ace Detective, but looking at the top row of Bjorn Thomassen’s liminality matrix, this game has a lot of it:

Almost every single character you meet in Persona 3 experiences change as the story progresses. Yet the ones who hit you the hardest are those who you discover are going through a transitory, life-altering event they have no control over. It might be their parent’s divorce; dealing with poverty; moving abroad; choosing to study what you’re good at versus something you love; dying from a terminal illness.

It’s not just liminality we experience through the story – there’s a lot of epistemic anxiety, too. That’s when you perceive a threat that undermines your understanding of how the world works. Think of all the questions you had about what the ‘new normal’ would be when the COVID pandemic began:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11229-022-03788-7#auth-Lilith-Newton-Aff1

I’m at pains to not spoil too much – there’s a lot of crazy plot turns after you reach the second semester, climaxing with the SEES squad having to negotiate a difficult choice that could either save the human race – or snuff it out forever. Up to this point, we’re witness to all of our protagonists going through heart-wrenching tribulation. We watch them learn to open up a little and protect each other from their weaknesses. They’ve had to grow up fast.

But they don’t negotiate. They all know as well as each other that the decision waiting in their future concerns the ultimate unknown. They feel epistemic anxiety at its peak. The lip of doubt wobbles. And at the same time, they’ve gone through so much already, few words are needed: they trust each other enough to go their own ways, and accept they’ll know their answers when it’s time.

When someone tells you “there is no alternative” to a problem, do you accept that at face value, because the solution will at least bring short-term relief? Or, do you expose it for the demand that it really is – “stop trying to think of an alternative?” There’s a right answer to this, and the SEES squad’s bonds are strengthened further for choosing it.

Gods, teenagers, and anime. It’s combinations of these three volatile ingredients that’ve given us Persona, Homestuck, D&D, every single Final Fantasy game6, most shounen mangas (pick one), Hades (the roguelike), Gurren Lagan, Dragon Ball, every creator whose work has been influenced by Dragon Ball, Evangelion, and motherfucking Death Note.

Persona 3 Reload was my first Persona game, my own personal rite of passage. The P3 experience is something that my friend Razzle has carried for over a decade. I knew – intuited, anyway – that it was something that came to him during harder times, and profoundly changed him. At first, though, I couldn’t make the journey – I couldn’t play this game because I knew it would upset me. I was afraid of reaching its destination, and what it would bring.

S. K. Kruse, in her presentation, The Art of the Liminal,7 highlights a familiar problem faced by artists – to do what we need to do, our mind has to enter its own liminal state, between consciousness and sleep. Yet, we resist going there, because we feel like we’re surrendering control of ourselves:

I know that I’ll be opening myself up to some force beyond my conscious control. Other voices will take over…

S. K. Kruse, “Art and the Liminal”

During the first third of the game, that manifested as taking everything in with “a sort of holy awe, but terror.” A work of fiction it might be, but P3 spares every moment, screaming at you, that here and now, it’s alive. I think this feeling came from knowing I was walking the path my friend had beaten years ago; when I told Razzle this, he immediately messaged me back; he was recommended P3 by an older friend who’d played it when it came out. He, too, had walked a beaten path.

Overcoming my fear, allowing the game to hurt me, was part of the journey. I can’t put an exact time on when it happened. It just did. It just changed me. What I can tell you is that the final day is the most beautiful ending to any game I’ve ever played. It rolls on slowly, to allow us to reflect, as we’re shown how the protagonist’s friends have been touched by his actions. Their lives move on, but it’ll be OK. They’ll never forget the meaningful impact he had on them.

It’s the end of the school year. The SEES squad gather on the roof one last time. Behind the rails, a stretch of ocean is combed by the spring breeze. Will they, come twenty or thirty years’ time, wear the scars of their sacrifices as they do today? When their echoes in the world die away, who will look after Aigis so she can tell their stories?

Perhaps that’s for the future to know. There’s no need to worry about it now. The clock has wound down. Up on the roof, a fragile stillness stirs, as a single moment, outstretched, lasts forever.

It’ll be OK. He’s reached his destination.

Pᴇᴏᴘʟᴇ’s ᴡʜᴏʟᴇ ʟɪᴠᴇs ᴅᴏ ᴘᴀss ɪɴ ғʀᴏɴᴛ ᴏғ ᴛʜᴇɪʀ ᴇʏᴇs ʙᴇғᴏʀᴇ ᴛʜᴇʏ ᴅɪᴇ. Tʜᴇ ᴘʀᴏᴄᴇss ɪs ᴄᴀʟʟᴇᴅ ‘ʟɪᴠɪɴɢ.’

Terry Pratchett, “The Last Continent”, p. 260

Though I can’t go into detail just yet, I’ve recognised my current rite of passage. The anxiety I feel is terrifying. I know what I do doesn’t matter now, but I have to pretend otherwise. It feels like I’m lying, and at the same time, there’s nothing to be deceitful about. I know what’s coming around the bend, but the more I think about it, the further away it seems.

Oh well. Guess I’ll enjoy the journey while it lasts. Once it’s over, I’ll have the Answer.

No, that capitalization wasn’t a mistake. The Answer DLC for Reload drops on September 10th. That’ll be the day after I– ah, you’ll hear about it soon enough.

- Image: Ben P L, CC-BY-SA 2.0, modified ↩︎

- If I actually wanted to go there, all I’d need is a visa, a return trip to the US, and a hotel within reasonable driving distance of 807 Oregon St. Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Through some excellent investigative work, the real location of the Backrooms has only been discovered very recently (May 2024):

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1G5rA1PseLZozA6oUYjdVN6Rn8GNdEVY7bTXV4SmVp7E/edit ↩︎ - And from that isometric viewpoint that most of the Where’s Wally? scenes are set. It’s the thing holding the composition together, I think. It’s not quite a bird’s eye view, but you feel like you see a bit of everything. ↩︎

- Maybe the anime has – I’ve watched very little of it, so I don’t know. ↩︎

- Adapted form found in the Wikipedia page, but the Thomassen’s original paper can be found here: https://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/2253233/22ab3f637146922a156651ebf1951964.pdf ↩︎

- Uhh… past this point, I asked around for ideas. I haven’t seen, read or played half of these, but I’ve at least heard of ’em. Thanks, Lattie! ↩︎

- Am I the only one who finds her delivery to be unintentionally Elizabeth-coded? Besides which, liminality would not be an out of character topic for residents of the Velvet Room.*

*(The only reason this isn’t featured in the main post is because… there’s not much to be said about it? The Velvet Room is a place residing between the conscious and the unconscious – by definition, it’s a liminal space.) ↩︎