- Note-taking’s a miserable task – notebooks and siloed documents in word processors aren’t the only tools at your disposal.

- Enter Zettelkastens – a method of linking notes together, built bottom-up, by you (with some general rules).

I wasn’t a prolific note taker in Uni. Don’t get me wrong, I took notes. I furiously hammered out bullet point on bullet point as though someone had a gun to my head. But when it came to coursework, I never used them. They were more like memos, or a bookmark you save to your browser toolbar and then leave for six months, by which time the reason it was important has long left for a jumbo jet and could not be further away.

One of my flatmates in first year dedicated much of his study to flashcards, and I soon joined him as it was clearly a hip, hot study hack to boost grades. On a good day, they were a helpful learning boost in the short-term. Most of the time, though I went back to do my drills like a bad rash I had to scratch – and if I scratched until I bled, the success I was entitled to would be reified – I’d become a real boy. It was the sort of feeling I got whenever I took cold showers to build ‘resilience,’ or meditated to be ‘mindful.’

In a word: taking notes, for me, was a miserable task, with seemingly little or no reward. See, the illusion of competence accounts for thinking we know what’s in front of us. If we cannot directly engage with our writings, then no matter how much labour we put into our notes, they become yet another thing that’s in front of us.

https://www.coursera.org/articles/illusion-of-competence

Here’s how I was introduced to note taking: Write things down; try to remember them; ???; hope they show up on the test; great, I passed; forget. The documents I wrote were bursting full of information, but with one crucial problem: all of that information was siloed into separate documents. Sure, I could analyse the ideas I thought were important, but there was no way to synthesise, or take two idea from separate lectures and see how they link up.

Tiago Forte’s most notable book, Building a Second Brain, opens with a statistic pulled from a New York Times article in 2009: Americans consume, on average, 34 gigabytes of information every day:

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/10/technology/10data.html

Fourteen years is a long time on the web. Suffice it to say that regardless of the veracity of this measure, and the soundness of the method used to acquire it, you can’t not be a voracious consumer of information today. But, as Forte claims, we tend to let most of this information pass us by. From social media posts, to Youtube videos, to reels on Facebook or Tiktok, everything is ephemeral.

With so much going on, then, it pays to curate what we find online, like fishermen dragging their nets through the water to score their catch of the day. In so doing, we can turn a critical eye to what we consume, and come to understand how fragments of ideas connect and coalesce into the bigger picture. Cory Doctorow describes pithily the evolution of the solution to this problem – writers have us digital iPad babbies beat to the punch since time immemorial with their analog commonplace books. Although they may not be organised, creators swear by them:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/09/the-memex-method/

Point is, if we have a tool that allows us to centralise the sources of information that grab our attention, we can explore that nagging feeling that “this is a piece of something bigger, and maybe something important.” That’s a great maxim for describing the nature of research. In my final year of Uni, I came up with my own: There’s no start, there’s no end, and there’s no yellow brick road. I’m researching all the time, trying things out, adding onto what I already know – it’s not some aspirational means to the educational end of getting a good grade. Open most webpages and you are tacitly researching something (even if the source is dubious, erroneous, or just plain batshit insane). I can keep track of everything I find in the one place thanks to two things: one, Obsidian, an amazing Markdown editor (other such applications are available); and two, Niklas Luhmann’s Zettelkasten.

My highly reductive mythos of the invention of Zettelkasten goes something like this: Luhmann finds boxes, and he indexes them; Writing notes, he goes, “Hey, I could index these notes too, and have them link to other notes;” he’s not just made an organised mess, but an indexed organised mess. Note 38a on Topic XYZ is an idea linking back to Note 17c, and Note 30b has got the same tags, so I’ll just go to that box, which is riiiiiiight over here…

https://zettelkasten.de/introduction/#luhmann-s-zettelkasten

In an even more reductive sense, Luhmann essentially curated a personal, curated web of information from his sources and his own thoughts, not unlike the World Wide Web, but before the World Wide Web came to be. It was hypertextual – he had a shorthand way of indexing that allowed him to continually refer back to earlier notes whenever needed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypertext_(semiotics)

In a word: he was linking his thinking.

A quick web search yields hundreds of links to people promoting their methods of establishing a Zettelkasten. One of its core principles, however, is that it’s a bottom-up structure: you are building the yellow brick road, brick and mortar, so beyond connecting ideas through indexing and tagging, how you organise the Zettelkasten is up to you. Its structural form follows its function – it’s for your eyes only, thus it expands to accommodate what you need:

https://indieweb.org/use_what_you_make

https://indieweb.org/make_what_you_need

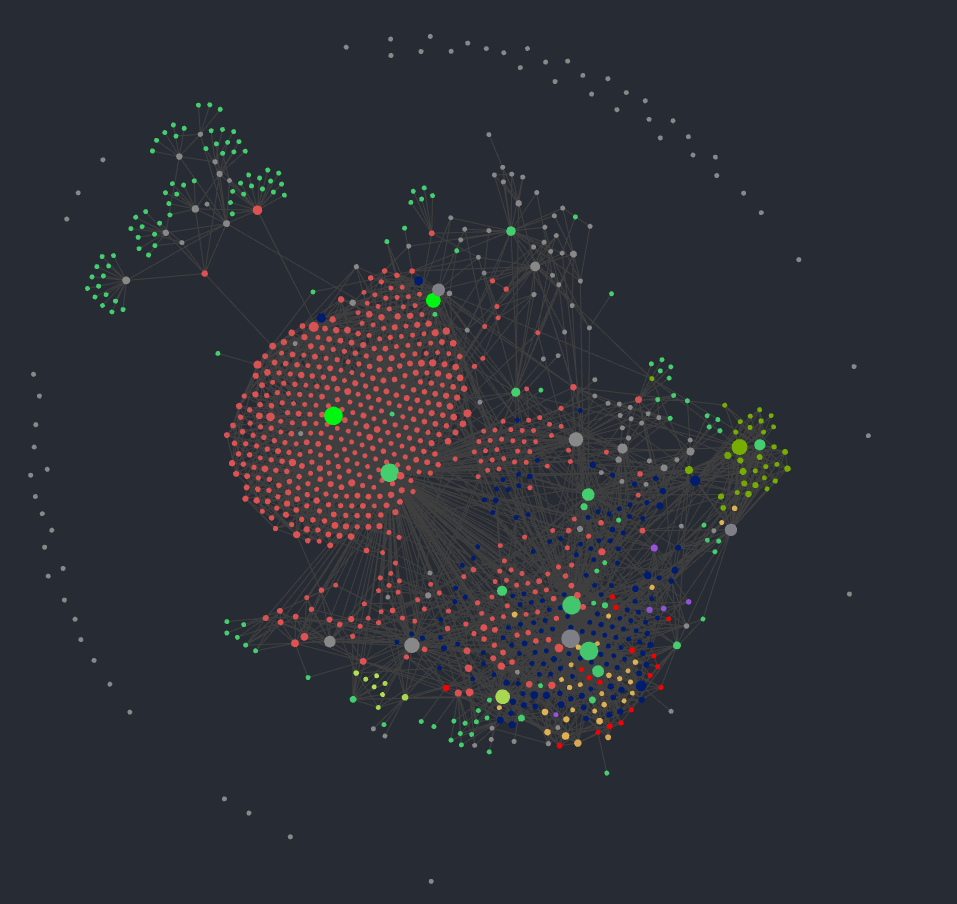

The image in the beginning of the post is what mine looks like so far. It looks erratic and insane, yes, I could take advantage of tagging things to make searching easier, YES, but it works for me, and it’s where I keep my notes on my various ‘involved’ topics that I fixate on in cyclic fashion – coding, pentesting, video editing, modelling, and so on. I try to stick to one concept per note (a principle of Zettel that makes interlinking ideas not mentally cumbersome), but I don’t have a perfect score on that.

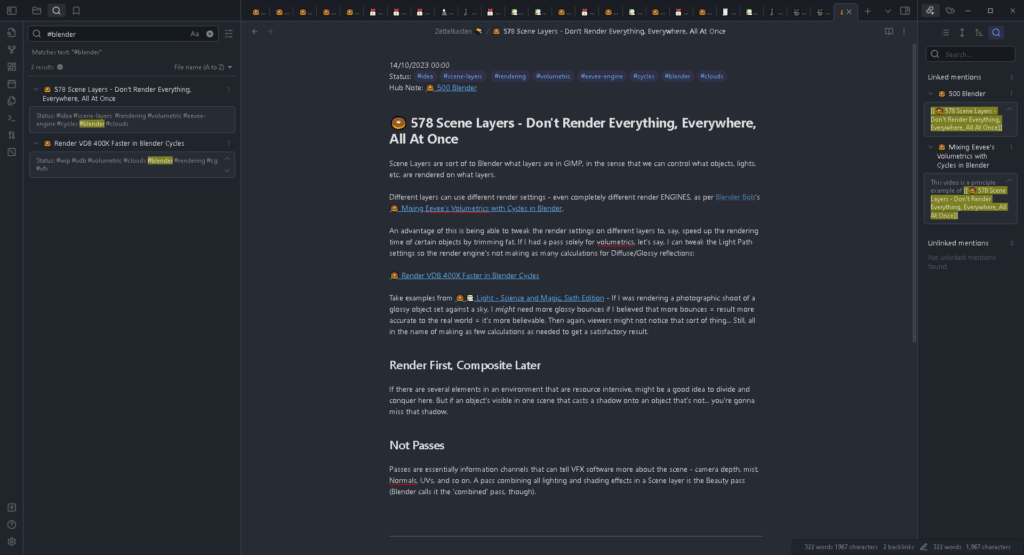

Obsidian is customisable in thanks to its community of plugin and theme writers. Mine’s pretty basic – the left panel is where I can search for full phrases or words (regex it supported); the right panel allows me to search through other posts that are linked to the post I have opened in the centre tab. There’s plenty of ways for me to customise my experience beyond this, but until now I haven’t really bothered. The toolbar on the far left is where I can access the node graph view. I must admit that I don’t really use it much – it’s more for show, really.

In the past year, I’ve accumulated hundreds of notes from the books and other resources I’ve read, and the thoughts I’ve had while reading them. Before making my Zettelkasten, I didn’t explore the questions that came into my head as much. It’s not that I was incurious – there was just too much stuff to look at. I still get this feeling whenever I go off and look at coding tutorials – there are a million and one resources out there, it’s hard to stick with just one. But when the web is so massive, you have to pick and choose if you want to build that yellow brick road. You might not reach the emerald city, but you’ll also never be going off in a pointless direction. What you end up finding may become pertinent in the near future. The Zettelkasten helps me build that road. It appeals to the spontaneity of browsing the web and synthesising ideas I pick up that traditional notetaking methods don’t.

There’s only one problem with my yellow brick road, however. Roads are infrastructure. They are a form of mutual aid that we build and maintain to help each other move around. My Zettel solved the problem of individual notes siloed off from each other, but introduced me to another problem – that it being for your eyes only is itself a kind of silo. What I put into the Zettel must produce an output of some sort.

Hosting my Zettelkasten online would be like hosting any other website. Take Soren Bjornstad, whose online solution for blog-cum-Zettelkasten is organised with surgical precision:

https://zettelkasten.sorenbjornstad.com

The way I’ve set mine up, that’s not really an option for me. On the other hand, the beauty of the blog is how one’s posts – a coalescence of ideas – interacts with an audience. A blog allows me to write about a run-on set of interlinking ideas in one place – something that short-and-sweet atomic notes can’t do. It just feels like they’re made for each other.

I don’t remember everything that’s in my Zettelkasten; neither did I remember everything from my notes at Uni. But whenever a new or interesting page claws its way through my eyeballs, it’s all the more rewarding when that little lightbulb in my head starts shining, and I go: “There’s something in the Zettel about this. This is a piece of something bigger, and maybe something more important…”