An 18-minute Zen on:

- Eye Dialect Reprise: Pratchett’s iconic character voices were made so through eye dialect;

- But.: And this is a big but;

- The Turtle Grows: “Cancelled” is just a euphemism for “I refuse accountability.”

Eye Dialect Reprise (permalink)

Character actions, rhythm of speech, vocabulary, and eye dialect. Combine those elements together, and we’ve got the masterful character voices that Terry Pratchett’s Discworld is known for. One way he often characterised was to have someone say a phrase in a language they don’t understand, but know the meaning of it. There are myriad examples:

“‘Tempers Fuggit. Means that was then and this is now,’ said [Nanny Ogg].”

https://www.lspace.org/books/apf/witches-abroad.html

Eye dialect helps when you’ve got multiple intelligent races who may quite literally be incapable of forming certain vowel sounds. City trolls don’t always pronounce their soft “th”s as a hard “d,” but not because they’re literally stupid – the warm climates of Ankh-Morpork make them sluggish, like a high-end PC in summer without any coolant2.

There’s a brilliant scene in Hogfather (1996) where Susan, a governess (and granddaughter of Death, dontcherknow) crosses paths with the esteemed guests of the Gaiter family’s dinner party. She, and little girl Twyla, are on the way to rid the cellar of a bogeyman.

Of course, no normal adult believes in bogeymen, not even two brandies into Hogswatchnight, so all they see is-

“Ye gawds, there’s a gel in a nightshirt out here with a poker!”

The deed is done, the iron poker is bent at right angles – the bogeyman is very real to Susan and Twyla, but to the partygoers, all they see is a nanny putting on a bit of parental bluster for a child who refuses to sleep:

“Ver’ well done,” said a guest. “Ver’ persykological. Clever idea, that, bendin’ the poker. And I expect you’re not afraid any more, eh, little girl?”

“No,” said Twyla.

“Ver’ persykological.”

Very unlike John Dufresne’s lecturing in a previous post, Pratchett punches up here:

https://brologue.net/2024/11/14/merely-hardly-to-dooly/

Dufresne warned us against ‘vernacular stereotyping,’ or accentism, bringing us out of the fictional world by making a character’s accent literally difficult to read:

This was, I suspect, a warning to his US audience, to leave such pejorative writing in the past, with Dickens, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Finley Peter Dunne’s Mr. Dooley, among others:

“A sthrateejan,” said Mr. Dooley, in response to Mr. Hennessy’s request for information, “is a champeen checker-player. Whin th’ war broke out, me frind Mack wint to me frind Hanna, an’ says he, ‘What,’ he says, ‘what can we do to cr-rush th’ haughty power iv Spain,’ he says, ‘a’n br-ring this hateful war to a early conclusion?” he says…

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22537/22537-h/22537-h.htm#ON_STRATEGY

But again, as per my last post, if you’re a Scottish person, writing for a Scottish audience, suffice it to say that we don’t give a fuck. Here’s the voice of God as spoken through Irvine Welsh’s pen in The Acid House (1994):

That cunt Nietzsche wis wide ay the mark whin he sais ah wis deid. Ah’m no deid; ah jist dinnae gie a fuck. It’s no fir me tae sort every cunt’s problems oot. Nae other cunt gies a fuck so how should ah? Eh?

(If it isn’t absolutely clear by now: if I, a white writer, were to introduce a black character in one of my stories whose words I spelled like this extract from the Baltimore Sun, that would be incredibly racist:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aunt_Priscilla.png)

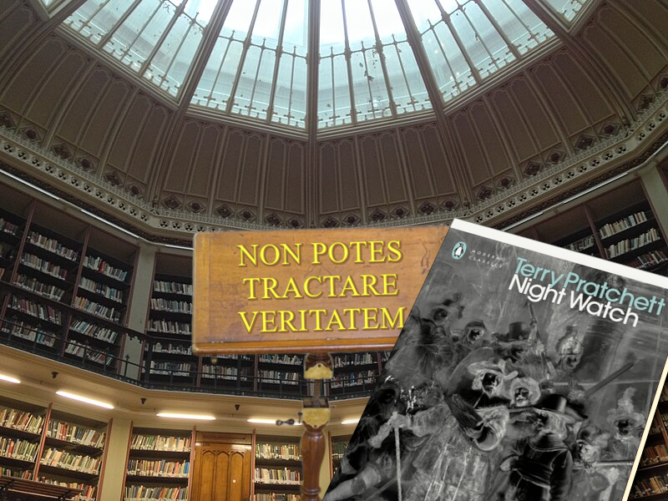

Back to Pratchett – much to the chagrin of the critics, who scoffed, and puzzled why anyone would read Discworld’s drossy, unchaptered, adverb-ladened prose, Night Watch (2002) will be re-released next April as an annotated3 Penguin Modern Classic:

https://locusmag.com/2024/11/terry-pratchetts-night-watch-re-release/

Teachers, you may now set Discworld as reading material without looking down at your feet, and without all the dirty looks. Lift your self-imposed embargo on the dreaded G-word: Discworld is now LITERARY FUH-FUH-FUH-FICTION. HIGH CULTURE, even – all it took was ten years’ hanging out with Death in a wicker coffin4.

That’s what’s happening on Roundworld – on Discworld, I imagine the shelves of L-Space coming apart, twisting and turning to make more room. Some shelves seem to pull back and disappear into the aether, only to turn up elsewhere. If you’re not careful in your local library, dive through the shelves, and end up on a side that isn’t a wall, you might find a stuffy, octagonal chamber that wasn’t there before. There’s a faint susurration of pages rubbing against each other.

The books in this part of L-Space are bound thrice with chains – save one. Perched on a mahogany lectern in the middle of the room, the annotated Night Watch draws your eyes to the golden Latatian inscription:

NON POTES TRACTARE VERITATEM.

The truth shall make ye fret: Detritus is HIGH CULTURE, too.

But. (permalink)

And there’s no arseing around this ‘but’ – when Discworld stopped being a fantasy parody, and started focusing on satirising our own world, Pratchett didn’t hit the mark every single time. When Pratchett missed, speech was about the last thing wrong with his characterisation.

Witches Abroad (1991) is one of my favourite books, because it’s an allegory of our tendency to believe in the stories we tell about ourselves and others, and how we often believe that things happen because stories said they should5. This is told through one of Witches Abroad’s many rich plot threads: through several scenes and discourse, we learn how stories physically manifest on the Disc, and how witches hold the power to bend stories to their own ends.

A good third of the humour in Witches Abroad (1991) is the use of eye dialect, false friends – or both at the same time:

“‘Der flabberghast,’ muttered Nanny.

‘What’s that?’ said Magrat.

‘It’s foreign for bat.'”

But Pratchett used it sparingly when writing in the voices of persons of colour. Two in particular – Erzulie Gogol, a black voodooist, and Mrs. Pleasant, a cook:

“Ye see that bit of okra?” said Mrs. Gogol. “Ye see the way the crab legs keep coming up just there?”

“You never were one to stint the crab meat,” said Mrs. Pleasant.

“See the way the bubbles is so thick by the okuh leaves? See the way it all spirals around that purple onion?”

“I see it! I see it!” said Mrs. Pleasant.

“And you know what that means?”

“Means it’s going to taste real fine!”

“Sure,” said Mrs. Gogol, kindly. “And it means some people’s coming.”

And about Mrs. Pleasant – “the first black person Nanny had ever spoken to.” Right on the heels of that sentence is Pratchett’s signature footnote:

Racism was not a problem on the Discworld, because—what with trolls and dwarfs and so on—speciesism was more interesting. Black and white lived in perfect harmony and ganged up on green.

So, it’s on human racism in Witches Abroad where Pratchett let his world-skewering satire curl up by the fire. Mrs. Pleasant, as an underdeveloped secondary character, fits uncomfortably within the Mammy stereotype:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammy_stereotype

She was a cook, so she bustled. And made sure she stayed fat and was, fortunately, naturally jolly. She made sure she had floury arms at all times. If she felt under suspicion, she’d say things like “Lawks!” She seemed to be getting away with it so far.

Witches Abroad intends to satirise what is essentially three British ladies on holiday, acting out their ignorance in a very, err, British way (Granny’s shouting at an inn-keeper to be understood comes to mind). It’s also got two example of Pratchett’s characterisation at its worst.

Sure, one might read Mrs. Pleasant differently – we learn from her that Genuans are being arrested for not meeting stereotypes:

“She’s shut up the toymaker,” said Mrs. Pleasant, to the air in general. “And yesterday it was old Devereaux the innkeeper for not being fat and not having a big red face. That’s four times this month.”

What if she’s supposed to be seen as a stereotype, either because the antagonist’s abuse of story magic has made her so, or she’s changed her behaviour to evade arrest? Sorry, but if Pratchett intended that, he would’ve made a great, red blinking point of it. He would’ve written something to suggest this, that this is bad, and that we should take the side against it. “Getting away with it” is too shallow to hold such deep subtext.

On the way to Genua (a cross between Oz’s Emerald City, Disney’s Magic Kingdom, and New Orleans), Granny and Nanny come across an ordinary, unmagical wolf that’s been anthropomorphised through story magic. But it’s still a wolf. It’s not a werewolf, as it can’t change its appearance. Besides which, werewolves are neither human nor wolf. But in stories, everyone expects the Big Bad Wolf to act human – they don’t expect him to act wolf. Or werewolf, for that matter.

If story magic dictated that all black Genuan women working in service must look and act like a Mammy or Aunt Jemima, just as innkeepers must be fat and have a big red face, or just as the wolf must act human against his own nature, then we should have been told. Instead, we got the footnote. And the footnote is all the evidence you need to know what sort of craft choice this was. We learn little about how Mrs. Pleasant changes in the story, if at all. She’s just a name.

That wolf gets more character development in one scene than Mrs. Pleasant gets in two or three. In the nicest of ways, when Pratchett falls short in Witches Abroad, it’s in those moments where it’s painfully clear that Discworld was being written by a white, middle-class bloke from Beaconsfield.

Beyond this footnote, racism is, in fact, a problem in Discworld. Just not in this book. Outside the other forty novels that make up the Lore™, David Graeber once noted that, when demi-human species are introduced to any fantasy universe, and cannot be unified under a cohesive social, legal, or political order, “racism is actually true:”

…There actually are different stocks of humanoid creatures who can speak, build houses, cultivate food, create art and rituals, who look and act basically like humans, but who nonetheless have profoundly different moral and intellectual qualities.

This is among other things the absolute negation of the bureaucratic principle of indifference, that the rules are the same for everyone, that it shouldn’t matter who your parents are, that everyone must be treated equally before the law. If some people are orcs and others are pixies, equal treatment is ipso facto inconceivable.

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-graeber-the-utopia-of-rules#toc10

And by “true,” what I think Graeber meant was this: fantasy writers, whether they know it or not, blur the mess about race that early anthropologists caused, and contemporary ones are still trying to rectify. On Roundworld, we now know that race is a cultural phenomenon, not a biological construct:

https://www.sapiens.org/biology/is-race-real

https://www.sapiens.org/biology/race-scientific-taxonomy/

This doesn’t stop folks who don’t know any better from assuming, based on apperances, that race is biological, judging that all the things known about genetics absorbed by “common sense” is a good enough heuristic. The minute you decide that humans live with, e.g., silicon-based lifeforms, the biological basis for racism is reified – a basis that, again, geneticists and anthropologists have refuted through the scientific method.

Since we can’t fit Roundworld’s anthropological constructs to a world of fantasy, writers usually co-opt the word ‘speciesism’ as a fine distinction from what we would understand as racism, and to help bring us into the secondary world the story presents to us. But when you get right down to it, to find out what it’s really all about, that trolls and dwarfs sling slurs at each other is an example of racism.

We can say this much: politically and socially speaking, Ankh-Morpork has got its shit together. Humans, trolls, dwarfs, vampires, werewolves, golems, zombies, Igors, the odd talking dog – all are welcomed to be bribed, robbed and murdered within its walls. Ankh-Morpork’s got the room for commentary like this passage in Snuff (2011):

And so one at a time we all become human – human werewolves, human dwarfs, human trolls… the melting pot melts in one direction only, and so we make progress.

Heavy stuff: you’re equals in Ankh-Morpork ON THE CONDITION that you act human. So surely there’s also plenty of room for bad, old-fashioned human-on-human racism.

Pratchett thought so, too. Jingo (1997) is a sharp rebuttal to, “Racism is not a problem on the Discworld.” Take the characterisation of 71-Hour Ahmed, bodyguard to the Klatchian Prince Khufarah. From Sam Vimes’ perspective, Ahmed acts every bit the stereotype, compared to the honourable, educated Prince. The eye dialect and clunky Morporkian comes out in full force:

“If hyou changing your mind, offendi, I give hyou twenty-five camels, no problem,” he said, pulling a clove from his teeth. “May your hloins be full of fruit.”

…

“I go, I hcome back,” he growled happily. “The Prince hsays the degree is Doctor of Sweet Fanny Adams. A hwizard wheeze, yes? Oh, how we are laughing.”

At the start, Ankh-Morpork and Klatch are in diplomatic dispute over what to do about the newly-emerged island of Leshp, smack-dab in the middle of their waters. We read the hum-drum, everyday racism and xenophobia through the mouths of Sergeant Colon and Corporal Nobby Nobbs:

“And o’course, they’re not the same color as what we are,” said Colon. “Well…as me, anyway,” he added…

“Constable Visit’s pretty brown,” said Nobby. “I never seen him run away. If there’s a chance of giving someone a religious pamphlet ole Washpot’s after them like a terrier.”

“Ah, but Omnians are more like us,” said Colon. “Bit weird but, basic’ly, just the same as us underneath.

Never underestimate anyone’s capacity to discriminate against foreigners over the tiniest things – especially Colon, the median voter in a ‘one man, one vote’ city state:

“…Whereas we’re more civilized, see, and we got a lot more stuff around to count, so we invented numbers. It’s like…well, they say the Klatchians invented astronomy—”

“Al-tronomy,” said Nobby helpfully.

“No, no…no, Nobby, I reckon they’d discovered esses by then, probably nicked ’em off’f us…anyway, they were bound to invent astronomy, ’cos there’s bugger all else for them to look at but the sky.

When the Prince’s life hangs in the balance, after an assassination attempt, Ankh-Morpork mobilises for war. Everyone suspects Klatch of a false-flag – everyone, that is, except for Vimes. He suspects his own fellow Morporkians first. Only later, when Vimes confronts Ahmed in Klatch, do we see that the Klatchian caliphate and its people are not, in fact, noble savages. Its government is just as ruthless as any other, to assassinate one of its own statesmen to justify a war over some rock.

At once, the switch in Ahmed’s character is a twofer: First, it’s a callback to his ‘foreign’ persona in Ankh-Morpork (he knows the city as well as any student of the Assassin’s Guild should), and this satirises how some folks view others through a blend of ignorance and hubris, armchair anthropologists who see foreigners as though they’re some art exhibit to be studied.

Second, Vimes’ reaction to realising he’s been well and truly had satirises those of us who have liberal fingers on our pulse – to see others right, no matter who they are, or where they come from. The Watch became a diverse force in Men at Arms (1993), and while Vimes grew to trust those different to himself, he didn’t fall off the other end of the spectrum with zeal. He sees colour/size/silicon/clay/vital signs par excellence, to the point where his entire beat is a free eye test.

Vimes might suspect the City’s character, but this, in its own way, still accepts the proverbial terms of debate that his fellow Morporkians establish: that the fault lies squarely in the character of a foreign country and its people. The real lesson, however, is that neither Ankh-Morpork nor Klatch trust their own citizens; in the first place, for states to justify fighting each other over stupid shit, they have to persuade Us that Them can’t be trusted.

Vimes reflects on this well before he confronts Ahmed, but it takes Ahmed for the penny to drop:

It was because he wanted there to be conspirators. It was much better to imagine men in some smoky room somewhere, made mad and cynical by privilege and power, plotting over the brandy. You had to cling to this sort of image, because if you didn’t then you might have to face the fact that bad things happened because ordinary people, the kind who brushed the dog and told their children bedtime stories, were capable of then going out and doing horrible things to other ordinary people.

It was so much easier to blame it on Them. It was bleakly depressing to think that They were Us. If it was Them, then nothing was anyone’s fault. If it was Us, what did that make Me? After all, I’m one of Us. I must be. I’ve certainly never thought of myself as one of Them. No one ever thinks of themselves as one of Them. We’re always one of Us. It’s Them that do the bad things.

It’s a far greater commentary on racism and xenophobia than Witches Abroad could ever be.

The Turtle Grows (permalink)

I’ve gone 3000 words without saying it: I will fucking suplex you if you think this post smacks of anything that suggests we need to “””””CANCEL””””” Discworld. No writer comes out of the womb aged 55, poised with the worldwise knowhow to write bestseller after bestseller. They grow. They change. New Discworld readers are told not to start with Colour of Magic and Light Fantastic for a good reason: parody ages fast, and spoils faster. They’ve never been Pratchett at his best.

But satire? Once you understand the world’s stories, and sympathise with the people those stories are about, a great satire never tarnishes. Peel back the verbosity, and Johnathan Swift’s Modest Proposal is as morbidly funny and cathartic today as it was nearly three centuries ago. Few, if any of us, no matter how pious, get it right the first time. So we grow; so we change.

Pratchett missed a lot in Witches Abroad that is to the story’s detriment. Left to the author’s trust in the reader to pick up what they’re putting down, the nuance missing in that story will always be problematic. And, at the same time, there’s evidence in the books that followed to argue that Pratchett, himself, knew of these problems, and strived to explore them with more nuance. He grew; he changed.

“If I’d written 25 versions of The Light Fantastic by now, I’d be ready to slit my wrists.”

https://www.lspace.org/about-terry/interviews/amazon2.html

“But how would he react if those books were published today–“

Millennium hand and shrimp with a side of rat onna stick, cease your vulgar non-sequitur6. He would be no different (OK, ten years wiser, at least). He was on Usenet over thirty years ago, before the Internet kicked off:

https://www.lspace.org/fandom/afp/timelines/afp-timeline.html

My 33mhz 486 is no longer a goshwow machine, Dell having done

their usual trick of waiting until I bought it before dropping the price

hugely.

You don’t even get 33 MHz in Fischer-Price toys, these days. And anyways, this video by Shaun puts it best. Long story short: Terry may be very dead, but the books show where his views on social issues lay:

To say so is not putting words in the mouth of the dead. It’s reading the words from his heart. And words in the heart cannot be taken.

Pratchett’s ability to discuss complex social issues through a fantasy satire series is something I hope to achieve in my own work:

https://brologue.net/2024/12/05/the-talisman-of-aubaum/

I may not get it right every time, but I hope to get it wrong better than most, change, and grow. And I hate the publisher monopoly as much as the next guy, but I’ll be buying that annotated edition of Night Watch when it drops next April, and reading it all again with relish. Mind how you go.

GNU Terry Pratchett

- Image: Fil Brit, edited, CC-BY-SA 4.0 ↩︎

- As far as human actions go for trolls, they’re Turing-complete – able to think any human thought, say any human word, make any human gesture, but like trying to run Google Chrome on the Colossus, they just take a bit… more… time:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colossus_computer ↩︎ - Of course, if if’s annotations you’re after, the APF is free for your perusal:

https://www.lspace.org/books/apf/night-watch.html ↩︎ - And a monopolist publisher to spoil the moment. ↩︎

- Put it this way: If stories on the Discworld are inorganic compounds, then their molecules are made up of atomic building blocks like, “third time’s the charm,” “slow and steady wins the race,” and “what you see is what you get.” Id-ions and moral-cules. ↩︎

- And, as it happens, a strawman, which yes, I’m quite fond of. ↩︎