In closing the Good Writers Tribunal, the judge sentenced an adverb to the guillotine for the crime of bad writing. It had been against the law to patronise readers. As it awaited its fate, the executioner asked if it had any last words.

“Verily,” it said.

The head rolled for two meters before it stopped.

On the one hand, writing ‘rules’ that ‘must be learned before they can be broken’ often omits more pressing questions. Who made those rules? Who must learn those rules? How are they to be broken? All of these are a matter of what Matthew Salesses defines as ‘craft’ – the decisions we authors make based on our audience’s expectations:

https://brologue.net/2024/09/11/we-do-a-little-crafting/

Two weeks ago, we had to read for class an excerpt from John Dufresne’s The Lie That Tells a Truth. He has, shall we say, a very clear vision for how literature ‘should’ be. But I found a number of his ‘rules’ to be things that do not match my experiences as a reader nor writer.

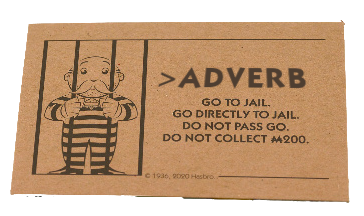

2. Adverbs

It’s a tale as old as time that when adverbs crop up in these books, it’s always about this specific form:

he said breathlessly.

he said arrogantly.

We spend so much effort pursuing the knowledge that will make us better storytellers, yet this most popular piece of advice tells us we need to show, not tell. What gives?

Just so we’re all on the same page – in the eleventh edition of Williams and Bizup’s Style – Lessons in Clarity and Grace, adverbs are described as words that “modify all parts of speech except nouns.” They write this in the context of longer prose, not dialogue tags, but I think the same principle applies.

Dufresne makes his stance clear:

A sign of a lazy, careless, or unimaginative writers. Dialogue should convey its own tone.

He’s got some carbon-60 cajones if he’s calling Terry Pratchett an unimaginative writer. Pratchett could never keep away from adverbs to save himself.

Dufresne makes it out like adverbs are the wasps of literature – noisy nuisances that don’t serve a purpose. He’s certainly correct when the action and adverb end up being redundant:

He ran quickly towards the window.

Running already suggests one is moving at speed. But let me throw you this curveball – a line from Pratchett’s Wyrd Sisters (1988):

“Come hither, Fool.”

The Fool jingled miserably across the floor.

Maybe you think a headpiece jingling miserably is as impossible as smiling your words. You’d be wrong. We’ve added a new piece of information that the reader might not pick up on otherwise. The ‘ran quickly’ version of this line would be:

The Fool jingled merrily across the floor.

(h/t carmina_morte_carent on Reddit for this one – https://old.reddit.com/r/writing/comments/10o6wxo/are_adverbs_in_writing_actually_always_a_bad_thing/j6fv8ey/?context=3#j6fv8ey )

Let me give you an example of some of my own adverbial ‘sins’ (adverbs capitalised):

William could sum up Painter in many combinations of four words or less, with or without expletives, but Painter managed to do it for him in just two:

“‘WEET PENT,'” he said, and committed to spell it out, and His Grace [The King] and Most UNWAVERINGLY Devoted [The King’s advisor] both agreed – you couldn’t read ‘WEET PENT’ wrong.

At that, the two men parted to either side of the hall. Painter excused himself and went along his way.

They came together again, and waited until Painter was out of earshot.

“Is he taller or shorter than the Courier?” The King said SOFTLY.

Could you infer, before that ‘softly,’ that the King didn’t want to be overheard? Is the advisor’s loyalty not already implied? As Salesses writes, from a craft perspective, tone in dialogue is implicit. You know what talking behind one’s back looks like ‘when you see it.’ What happens when the reader doesn’t know it when they see it? Do we shrug our shoulders, throw up our hands and say, “That’s a you problem?”

I will say, that as an autistic person, between tone, actions, and dialogue, sometimes I’ve completely misread a scene only to have to retrace my steps much later in the book. What I don’t know is if an autistic audience prefers adverbs because the emotion is made explicit. Maybe the next time I go to read, I’ll make a note of when this happens.

Let’s turn our thinking around. Adverbs are not something to be avoided, but tools that are hard to use right. We’re already in abundance of examples that show when they’re not the best tool for the job:

https://www.fantasy-writers.org/content/adverbs

https://fantasy-faction.com/2012/writing-rules-and-fantasy-adverbs

If they’re hard to use right, might there exist a setup where using one after a dialogue tag would have maximum effect? Likewise, there must be an audience for whom the use of adverbs offers the clearest window into your world. Who are they?

Another thing adverbs do have going for them is that they’re economical. You could spend twenty, thirty words describing an action, and trust the reader to interpret it as a sign of anger – or you could trade in that imagery for a single word, and trust the reader knows what ‘angrily’ means.

That’s what I think about adverbs – and I agree with the line of argument that dramatising character actions can and do say more than adverbs could. I can’t stand wasps, but we need them as predators and pollinators.

6. Pronoun Before Attribution

Dave said, not said Dave.

There’s a very meticulous, anal retentive sort of reader who looks for this in fiction with a nagging twitch. They are not my audience, and they probably never will be. But if needs must, the next time I read a story where the writer commits this horrible sin, I’ll be sure to leave a 1-star review on Goodreads and attach a thesis.

8. Eye Dialect

For as long as I could remember, my Nannie was hearing-impaired. We wid aye spik in the local wey a daein, and then, when she couldn’t hear us the third time, Mum would always let the thunder roll in the Queen’s English. It was heard clear by then. If Nannie thought speaking ‘proper’ English would get her children far in life, she never told me so.

I know Scots is technically a language, but I’d put money down that you’d be hard-pressed to find a Scottish person who respects spelling rules when writing words as they’d be said. There are so, so many words we use in our house that I’ve heard my entire life, yet neither me, nor my parents really care for the correct spelling. ‘Fandabidozi,’ ‘fandabbydozy’ – potato and potahto:

Me: Hanover Street, oshahoorsir (TL: oshahoorsir is an interjection similar, but not identical to the Irish phrase, ‘cute hoor.’)

Mum: Nice x

Me: I do not post photographs of my food often… But this was 𝓐𝓝 𝓐𝓕𝓕𝓐 𝓣𝓡𝓘𝓣

Dad: Yes, you’re good to yourself x

Suffice it to say that Dufresne and I have very different experiences and understandings of eye dialect, but the other funny thing about Scots (language, and dialects) is that, somehow, anyone who isn’t Scottish spells it woefully wrong. I can’t explain this paradox – I just know that this:

Why dae folk as babies stupid shite lit “Ur getting big arent ye?” As if the wee cunts gony be like aye Moira yer spot on am oan the protein

This was written by a Scottish person – and this:

why does somebody not know how to flush the toilet after they’ve had a SHET?

…

well it was FOOKIN one of yus…DISGOOSTANG!!!

This was written by somebody who’s heard a Scottish person.

Two things are made very clear from Dufresne’s diatribe on eye dialect. First, he’s not writing about eye dialect, but a form of discrimination called ‘accentism:’

Second, for all he warns about ‘patronising’ the reader, the manner in which he eschews this technique is, ironically, obtuse and patronising:

Anyway, trick spellings and lexical gimmicks are the easy way out. Not the best way. When you use unusual spelling, you are bound to draw the reader’s attention away from the dialogue and onto the means of getting it across. What could be the point of spelling a word as it’s pronounced—was as wuz, or women as wimmin—except to look down at the character? Characters don’t spell as they speak.

Where we might agree – as one of my cohort pointed out last week – is that a character’s actions, rhythm of speech, and vocabulary can also be used to flesh them out. They gave James Joyce’s Ulysses as an example. I’ve never read it, and I know it’s a book where the pages have staled by the time you’re finished, so Wikiquote, guide my hand:

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Ulysses_(novel)

At the same time he inwardly chuckled over his repartee to the blood and ouns champion about his God being a jew. People could put up with being bitten by a wolf but what properly riled them up was a bite from a sheep.

Eye dialect absolutely can be used to ‘other’ a character, or a group of characters. I just think there’s something bigger, and more important, going on in a story that causes it to go astray.

(It’s here that I would have gone on a tangent about PICNIS – “Problem In Character, Not In Speech” – and focused on Pratchett’s characterisation at its worst, but it kept growing, and it’s big enough to be its own post now.)

11. Scatological Language

“Scatological language may show that the author feels contempt for his characters or has sold out to what he perceives are the demands of the marketplace… Don’t think you’re shocking the reader with strong language.”

“Do the cogs of capitalism make us so out of touch…? No, it’s the writers who are wrong.”

The only way I can make sense of this advice is to imagine that, in his youth, Dufresne had a chance encounter with Mary Whitehouse. She must’ve set about him with a tongue-lashing on all the indignities of indecent media today; schismogenesis took its course, and a lifetime of writing later, he arrived at a semi-agreement, that bad writers make the President swear because they are a person in power; we’re meant to hate them because swearing and power go hand in hand.

17. Adverbial Clauses

I don’t know what the point is here. An inferior writer “thinks that each character has to earn the write to speak by behaving as well?”

“I’ll get the door,” she said, as she crushed out her cigarette and stood.

Ah, but the writer who doesn’t pin action to dialogue writes it like this:

“I’ll get the door,” she said. She crushed out her cigarette and stood.

The exact same sequence of events occurs in both lines. Not only that, but the time it takes for her to say and do these things is virtually the same. The only difference is that, in the second example, the three actions are split into two clauses: her speaking (verbal), then crushing the cigarette, and standing up (both nonverbal).

I can see an argument being made for run-on adverbial clauses, that might describe how someone’s behaving in the middle of a conversation, but also takes us out of story time2. Again, allow me to return to my King and his advisor, who are walking down a hallway and exchange a bit of banter about someone they know – suddenly, the King makes an outburst:

“No, he’s not the best, he’s Roy’s best!” The King snapped. “A Pawn, and a dwarf into the bargain!” It was like ordering paella and ending up with a papaya – nice enough in their own ways, but not what you asked for, and in the latter case, certainly not a meal fit for a king. “Suits! All brains about money, no common sense!”

The scene builds up to this outburst – and then the narrator cuts in with this comparison between paella and papaya, interspersing the anger. You could argue it gets in the way of the emotion – that anger should come all at once, lasts as long as it needs to, and as soon as the outburst’s over, the scene returns to its normal pace and tempo.

[THIS CONCLUDING PARAGRAPH LEFT (MOSTLY) BLANK]. It’s not that there’s a lot of work for me to juggle at the moment, but I’m finding it a bit much to handle and string sentences together at the same time. Maybe it’s just that time of year again…

- (Image (edited): Science History Institute, CC BY 4.0 ↩︎

- As per the definition in Anna Keesey’s essay, Making a Scene – story is when we experience the events of the plot through the eyes of some character; discourse is how the writer chooses to show this to the reader; when discourse time equals story time, an action or conversation takes as much time to read in your head as it would to act out. That, friends, is what Keesey defines as a scene.

You could write a sentence describing a chess player’s opening move. That would take as much time as it would to move that pawn out to e4. Or, you could write a long, literary paragraph for the Higher English students, who’ll end up having to study it for exams, about the chess player’s inner turmoil, trying to think as far ahead as they possibly can the possibilities that open after 3. Nf3 or 3. Bb5. ↩︎