- Models: Easy to teach, but don’t mistake the map for the territory…

- Asking the next question: A little tip you might find useful in your next writing endeavour.

I’m always very skeptical of the idea that we can create a model that can explain all of fiction. I don’t mean to say that literature is some esoteric magic that, no matter how far down we go, can never be truly explained. Joseph Campbell spent seven hundred pages describing his hypothesis that all stories are connected by common symbols, and then threw his hands up at the end just to say, “idk guys, i’m just spitballing:”

https://brologue.net/2024/08/08/monomyth-when-it-sees-the-surroundsoundmyth/

No, it’s perfectly possible for us to explain how storytelling works – we just have to simplify things a bit using models. By creating signs that we can point to and derive meaning from, models make creative writing easier to teach (which is a good thing!). They are to literature what dioramas of the solar system are to the actual solar system – maps to describe the territory.

Once you start using models to analyse anything, however – not just literature – you risk mistaking the map for the territory. No matter what a model is for, when you abstract something complex into a simpler model, it is always a lossy operation. If you view a story as purely a set of symbols to be mixed and matched, then of course it’s been done:

Friends don’t let friends mistake the map for the territory. The Monomyth can’t tell you the differences between the Aeneid and Watership Down, but what your fleshy, qualitative human friends can tell you is that, while they share superficial similarities, the latter’s story is made far richer if you’re familiar with the former:

https://owlcation.com/humanities/How-Monomyth-Theories-Get-It-Wrong-About-Fiction

One of the things we had to review for this week’s seminar is a primer on writing short stories by Mary Robinette Kowal, and yes, I was quite skeptical when she presented a model that she claimed explained all of fiction, non-fiction, etc.:

The ‘MICE quotient’ – milieu, inquiry, character, event – is really just an acronym encapsulating four common story threads that, to quote Ron Carlson, drive the motor of fiction – the series of images that bring us from one point to another. Most stories have several of these threads running in parallel, and Kowal compares this to the opening and closing of HTML tags.

Here’s something I came up with: Your character goes to the library (M) to find a book that might explain a burning question (I), but the library’s closed, and the only other place that might have that book is a bookstore in the centre of town (/M). So, they go to figure out when the bus comes (I), only to find the bus stand has been levelled by a storm (/I – it happens!). OK… just Google it and– great, their phone’s died. When it rains, it pours. Repeat and intensify to farcical levels.

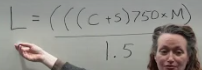

Then there’s this whole wordcount formula Kowal’s got going on:

It’s a heuristic wrapped up in the language of mathematics. The use of maths symbolism really interests me more than the formula itself. We know it’s very fuzzy logic, and no-one would seriously assert that the length of a short story can be empirically measured using these variables1… but using that maths frame, it gives us that little confidence boost, that because we think we can measure it, we know when’s a good time to wrap things up. Less characters/locations, less words.

(As for why this framing gives us the confidence it does… Well, I’ll leave that one for the anthropologists to explain.)

One rule of thumb that our tutor has drilled into us is what I’ve dubbed “wedge theory.” As I’ve understood it, wedge theory goes like this: take your character’s life, partition it into wedges, and pick the wedge with an event that irrevocably alters what has been, and forever taints what will be; start writing from there. The author Charles Baxter2 describes a similar heuristic called ‘undoings’ (in an essay of the same name):

https://coloradoreview.colostate.edu/features/undoings/

Your character is inevitably going to do something that they can’t undo. In character-driven plots, that decisive action is the main thread you should pursue.

Particularly when it comes to sci-fi, fantasy, speculative fiction, weird fiction, etc., there’s one great aphorism that comes to us from Theodore Sturgeon – “ask the next question:”

https://christopher-mckitterick.com/Sturgeon-Campbell/Sturgeon-Q.htm

Rather than a character, take a technology that perhaps already exists, or is speculated to exist in the near future, and ask questions about how it shapes society for better or worse. What does it do? Who does it do it for? Who does it do it to? In what ways might we use it different to what the designers expected? We keep asking the next question until we have a sufficient list of plot points that our characters run into.

I would’ve provided another example myself, but as I was writing this, I came across this superb piece of satire on Mastodon:

https://infosec.exchange/@SecureOwl/113227069429183637

I think it executes the principles of MICE and asking the next question pretty well. Two cops want to raid someone’s home, and the writer essentially keeps asking:

- “Beyond needing a search warrant, what technology can I put between them to make it harder for the cops to deliver the search warrant?”

- Why is that technology not a sufficient solution, and what’s the workaround?

Kowal calls these attempts by the police to enact their search as ‘try-fail’ cycles; the ‘armature,’ as Brian McDonald describes in his book, Invisible Ink, is that the unaccountable power of unnecessary middlemen binds even those who are supposed to uphold the law. Thus we subvert the time-honoured conservative adage:

There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.

https://crookedtimber.org/2018/03/21/liberals-against-progressives/#comment-729288

It makes you think of the forces in your daily life with power beyond those who are supposed to uphold the law. As servants of public law, the cops could change your life with a little state-backed violence; all HP has to do is control how, when, and how much we print with a remote software update. In the world of private law, the cops and the suspect are both bound by a company who designs their printers to be – how do they put it? Ah, yes – less hated:

The story could easily continue: what if said update wasn’t properly tested, and caused mass printer failure? What if the cops now have to find another printer, but all the ones not bogged down by shitty DRM and pointless printing apps are being sold at a 1000% markup by scalpers, and the department just doesn’t have the budget for that sort of thing?

If only they’d just gone straight to the judge and asked for a search warrant in her own writing. Unfortunately, by the time they realise this, the judge has just had cataracts surgery in both eyes and is on sick leave.

That, right there, is the power of asking the next question.