A little 9-minute something about:

- Epistemic anxiety: When you fear that there’s a lot more to how you know what you know… that you don’t know;

- Craft: Expectations of what your stories should contain that your audience will love

As of Monday, I have become a student once again, studying for a postgrad in creative writing at St. Andrews Uni. Though its prestige slakes the throats of those who utter its name; though it was some divine institution responsible for birthing many of the world’s wealth-makers; I’m not enraptured by St. Andrews because, well, I’ve seen it before. It’s not Hogwarts, it’s the Unseen University – “now you see me, now you don’t.” Day in, day out.

If I’m in a really bad, irritable and cynical mood, I’d tell you the sole reason I’m doing this degree – no more, no less – is to get those who think I need it to be a writer off my back. Sometimes, it feels like your academic record is the only heuristic recruiters know to use:

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Credentialism

And sometimes, you just plain don’t know what the fuck it is those rejection emails want:

https://brologue.net/2024/04/25/stare-at-screen/

But that’s if I’m in a really bad mood. The more important reason is that COVID incinerated anything that was left of the shrivelled corn kernel I’d called a social life until that point. This is an opportunity to meet people whose experiences are vastly different to my own – and whose said experiences I need like air, or water, or Bo.

There’s so much I’ve yet to know, and I think this is what I attributed to my writing ‘funk’ in my last post:

https://brologue.net/2024/09/05/the-peaming-of-peamssac-epeamphany/

I am on the precipice of exiting one terminal and entering the next, the fast-approaching event horizon that spaghettifies ‘what will be’ into infinity, leaving behind ‘what is’:

https://brologue.net/2024/06/14/the-liminal-is-the-means-by-which-all-is-revealed/

I know I’m going to have my nose to the grindstone for the next year and a half, but, y’know, these petrifying emotions have afflicted me before – all of us, in fact. COVID was a catalyst that gave us all the watery brush that comes with confronting epistemic anxiety. At the start of the UK lockdown, we were closing our eyes, and pinching ourselves, hoping to awaken from a dream, only to open them to the constant stimulus of waking nightmare.

Pots and pans crashing in the street, clapping for carers, supply chain disruptions in every commodity from computer chips to bog roll, dystopian remote invigilation software (coming to a smart device near you!), living at work…

…No, fuck off with those ellipses, I’m not done yet; we were then treated to BoJo’s Winston Churchill tribute act, propped up by the sheer vapidity of The Thick of It extra and then-Leader of the Opposition, Keir Starmer; lockdown parties for the rich; record-breaking profits; more accolades for the hottest year on record; the housing-energy-cost-of-living crises; are you wondering where the climax is? So am I! It keeps happening!

No-one knew when we would be able to safely go outside again, or if how we would interact with the world would ever be the same. COVID uprooted every preconception about ‘how the world works’ – our epistemology; our ‘how we come to know what we know’ about ‘how the world works.’ That, friends, was epistemic anxiety on a global scale.

It was Christy Harrison’s ‘The Wellness Trap’ that first introduced me to epistemic anxiety, and it was by complete accident, as I was gathering sources, that I stumbled upon a paper that turned out to be far more relevant to a friend’s TESOL studies:

In this study, another epistemic emotion, curiosity, is studied. The researchers found that one can hold epistemic curiosity and anxiety simultaneously – they’re not binary. We can be inspired to go out and seek novel knowledge, at the same time as we are self-conscious and doubtful of what we have come to know, through our own experiences, weighed against the material put before us.

This latter point is the spectre haunting the first few chapters of Matthew Salesses’ book, Craft in the Real World. I suppose ‘craft’ is to new writers what ‘fundamentals’ are to new fighting game players – you’ll see folks throw the term around, but to you, the newbie, it’s nebulous, perhaps even arbitrary, until you slowly come to learn what it is by interacting with other people.

What we would call ‘craft’ is, first and foremost, a set of storytelling expectations, heuristics that we use to develop tastes on what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ writing. Western audiences collectively groan at the deployment of a deus ex machina, the apex of coincidental plot points, storytelling’s public enemy #1; why is that so? What makes stories plotted by causation and agency more compelling to us than those plotted by happenstance?

Or, consider word choice1: why do our school teachers go to such great pains to get us to use words other than ‘said’ when characters speak, when just about every single author commits what, at that point in our lives, looks to be literature’s original sin? Well, firstly, it’s to build vocabulary, but secondly, unless a character has to deliberately modulate their voice (a shout, a shriek, etc.), dialogue tags are invisible. ‘Commented’ would have just as much effect as ‘said.’

Except, if you, the average English reader, were to read an entire novel, or short story, where ‘commented’ was used entirely in lieu of ‘said’, you might find it puzzling. Suppose, then, you were to encounter this writer as a fellow student at a writing workshop; they might be from a different cultural background, but for reasons best known to themselves, they continue to use ‘commented.’2 Clearly, it has quite a different effect on you – and the rest of the workshop, too.

“Why won’t they just use ‘said?'”

This is a toy example of what Salesses considers to be ‘craft.’ That writer isn’t necessarily writing for the same audience as you. Their audience is one for which ‘commented’ is just as invisible as our ‘said.’ Everyone else in the workshop, being used to ‘said,’ share a cultural background, an idea of what ‘craft’ is. The latter writer does not. Craft is not as monolithic as it appears.

Of course, for some, craft is to be exactly that: monolithic, compromising to the widest demographic possible such that when your book goes to market, it should, in theory, have maximised the number of eyeballs looking at it. But for Salesses, a Korean American, he’s been on the receiving end of workshops teaching craft that goes against his experiences; through his research, he’s found that trying to appeal to everyone often comes at the expense of those voices who ought to be heard.

Let’s return, briefly, to the Monomyth:

https://brologue.net/2024/08/08/monomyth-when-it-sees-the-surroundsoundmyth/

Now, Campbell conceded in the epilogue of The Hero With a Thousand Faces that, for the past several hundred pages – despite all the rhetoric and evidence he put forward to argue for the Monomyth’s existence – he’d just been spitballing. Be that as it may, I think the opening line of his epilogue is out of place; it’s hiding in the back, far from opening the prologue, and his spiel about his “aloof amusement” towards “bizarre” tales, and “mumbo jumbo.”

Keeping Salesses’s ideas in mind, consider that, for all intents and purposes, The Hero With a Thousand Faces could be interpreted as a manifesto, laying down Campbell’s arguments for the development of Western craft in the post-war period. It was published thirteen years after the establishment of the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop, the first Master of Fine Arts program in the US.

Though Campbell was never involved with the Workshop (to my knowledge), his Monomyth and the Workshop’s prioritisation of style and form in creative writing do have something in common. Salesses’s source on the Workshop is Eric Bennett, associate professor of English at Providence College in Rhode Island, and author of Workshops of Empire, a history of American creative writing during the Cold War.

Bennett writes that the Workshop’s impact on style and form rejigged craft to value storytelling that was individualistic, apolitical, timeless, and formulaic (in the sense that said stories could be added to the curriculum of any school and be taught the same way, anywhere). Salesses summarises it thus: “It made literature easy to fundraise for, and easy to teach.”

On craft setting an expectation that writers of minority backgrounds should switch audiences, juxtapose this with George Yule’s comments on language planning, which I covered in my essay, ‘WTDWA?’:

https://brologue.net/2024/06/21/wtdwa/

When educational material is being written up for schools in areas where people speak multiple languages, one inevitably rubs against the question of which language to set it in. In the southern United States, for example, there are lots of places with an mix of folks who speak fluent Spanish or English3. Trouble is, no matter what language you go with, you’re asking a not-insignificant number of kids to do extra legwork to keep up.

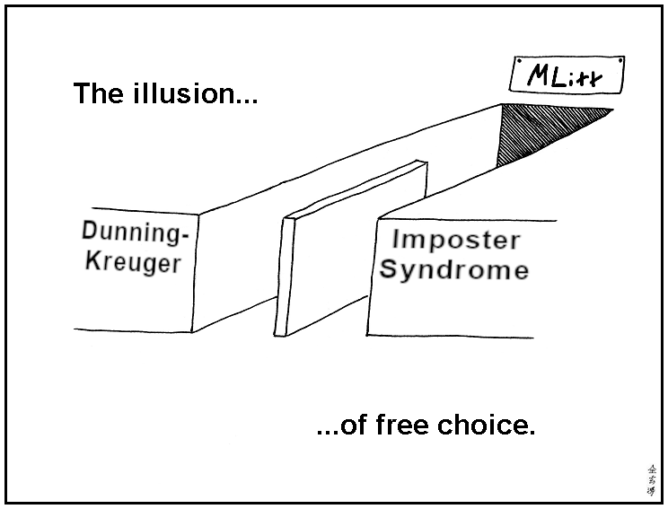

Acknowledging your peers’ experiences are far different to your own piques my epistemic curiosity, but it also makes me anxious, and self-aware that there’s so much I don’t know about my own writing process. Until this point, I never really considered highlighting race in my characters, because, though I am a neurominority, I’ve never been discriminated for being white. I’ve never experienced the microaggressions that people of colour do. It’s something I’ve never had to deal with.

I thought, naively, that “well, the reader can imprint whatever they want about the characters’ races, because my story is about a fantasy world where the only interesting bigotry that’s left is what side of the dividing line you’re on: Black Army, or White Army.” I know that’s the colours of the pieces in chess, but come the fuck on – dark and light are right fucking there. A real “share if you don’t think” moment if I ever had one.

Everyone who knows me personally – my parents, other members of my family, even my old English and French teachers – thinks I’m going to smash this degree, but their support, while I appreciate it, is not so anodyne as it may seem. I’m not just going from being a student again to graduating next year – I’ve got work to do inbetween. And it needs to be done with courtesy, and grace, and account for the things I have been privileged enough to not worry about.

Consider that the fourth pledge missing from this post:

https://brologue.net/2024/06/20/i-just-make-stuff-up/#anthro-vision

Let it be known that Brologue’s not going anywhere. In fact, it might even be livelier than ever before. Watch this space…

- As I considered when the panel at our welcome ceremony repeated, multiple times, that we had ‘won’ our placement at St. Andrews. I don’t recall putting my name into a tombola to be chosen at random. ↩︎

- In the book, the word Salesses chooses for his thought experiment is instead ‘query.’ The penny’s only now dropped for me, that there’s a clear allusion to ‘queer’ here; I’m now put in mind of the sort of person who says they don’t have a problem with ‘the gays,’ just so long as they keep it in the closet and don’t make it their entire personality (the volume of behaviours that make such a personality, of course, is decided by the person who is not gay. This is irony, by the way.) ↩︎

- I would be remiss if I didn’t include a link in this post to Nancy Friedman’s latest Fritinancy post on Spanglish advertising in the San Francisco Bay area:

https://fritinancy.substack.com/p/spanglish ↩︎