- CONTENT WARNING: Sex, BDSM, questioning authority.

- Part I – Dave Gorman: or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Look Closer;

- Part II – David Graeber: A quick(ish) rundown of the moral injury of working in a bullshit job on someone else’s clock;

- Part III – The Amstrads: Use your foe’s advertising against them;

- Part IV – The T-shirt: What to do when the custom T-shirt website won’t let you mention the boss…

This was originally a post about getting a shirt company to print a design that it told me it wouldn’t print, despite the fact that it hosted several other designs pointing to the contrary. It has developed into a much longer post, because I felt it necessary to go through Chapters 3 and 4 of Bullshit Jobs for those who haven’t read the book.

Look, here’s the TL;DR – https://geekdom.social/@bigolifacks/111536433069967214

Part I: Standing on the Edges of Rules

While I hate being told ‘no’ in ways that don’t use the word ‘no,’ I love taking the long way round to find out why. Sometimes, I might find ways of bending that ‘no’ back into a ‘yes.’ This is the sort of curiosity that drags most hackers by the scruff of their necks. The term today is colloquially used to refer to ‘that guy wot is good with the computer,’ but back when we first started to use it in a computing context, it meant someone who was able to rework something to their advantage.

Hackers know how to stand on the edge. Particularly, the edges of rules. We’re interested in how something works insofar as using that knowledge to figure out how that thing breaks, and fails. The same could be said of observational comedy. A good comedian knows how to stand on the edge and tease out the mundanities and benign, nondescript actions of everyday life and show the audience how utterly bizarre they are.

Dave Gorman: Modern Life is Goodish deserves a spot as one of the best comedy shows produced for television in the past decade. Gorman pulls up the floorboards of our society of rules, mocks them by doing something that takes them to a logical extreme, and it’s rip-roaringly funny. How can we trust the red balls embedded in our dishwashing tablets haven’t been Smarties this whole time? Why do you advertise your service as being 4.5 stars out of 5, but your graphic clearly shows 4.9 stars?

The whole series is available on Gorman’s YouTube channel, where he also hosts clips for his panel show, Terms and Conditions Apply (Which is really Modern Life is Goodish but as a panel show):

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCwbqOKXhYrZEyMcLh4oVEIg/playlists

Something similar could be said of the late anthropologist David Graeber and his incredible 2018 book, Bullshit Jobs. We find no end to ‘shit’ jobs in the modern working world. You may hate part of, or all of your job. But a truly bullshit job, by contrast, is one that “is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious, that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case.”

There’s many parts of the book I could write about at length, but one that keeps returning to me is why people who have bullshit jobs feel so unhappy. See, if bullshit jobs were utterly pointless and paid poorly, that would make sense. Graeber cites a couple of studies that suggest there’s an inverse relation between social return on investment and the amount that workers get paid that needs investigating:

https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/8c16eabdbadf83ca79_ojm6b0fzh.pdf

If the world woke up tomorrow and found that its school teachers, nurses, cinema staff1, and tube workers had all vanished, that would be a far greater crisis than if, say, all of its corporate lawyers had dispersed into vapour.

The more bullshit the job, the more likely one is to be paid handsomely for it. What’s the issue, then? Most people would kill to have a job where they get paid six figures to pretty much sit on their arse for seven out of eight hours.

The anecdotes Graeber presents come from an email inbox created in response to an earlier article he wrote for STRIKE! Magazine:

https://strikemag.org/bullshit-jobs/

Interestingly, of all the people who emailed him with their story of having a bullshit job, few of them expressed the happiness we might expect. Chapter 3 explores the case of Eric, a working-class history graduate who, having sat on the dole for six months after graduating University, landed a job in IT admin so pointless, and yet so undemanding, he could’ve been set for life.

A history gradute… in IT? If he wanted to go into academia, it’s a head start. Eric found, however, that his job was essentially to develop a collaborative interface for the company and its partners (he had no IT experience, mind), maintain it, and to market it to staff. The interface was a madcap idea from one of the company’s partners: the software they’d bought to build it was as cheap as they could find, and because it was bossware, not a single employee wanted anything to do with it.

In a word: some middle-aged manager saw the CV of a twentysomething white kid, saw the history degree, but given his age, thought, “Ah, he’ll be good with computers, and if he’s not, at least I’ve got someone on the job.” Eric was employed to tick a box, not to actually do anything about a fringe infrastructure project that was dead on arrival.

At first, the acts of rebellion were small, but eventually built to “lunchtime walks that lasted three hours;” when he tried to quit, his boss offered a £2,600 raise. The rebellion ramped up – fake meetings and day-long pubcrawls with friends that sprawled into the night. Forget burning the midnight oil, they might as well have quaffed the lot and bashed the side of the lamp to get the dregs out.

The rebellion ramped up. So did the boss’s raises. Eric was paid to do a job that, at most, required him to answer the phone twice a day – and he was absolutely miserable.

The way I’ve retold this story may make it seem like the only person responsible for Eric’s misery was himself. This seems like common sense. But common sense doesn’t answer the critical question that Graeber raises: Someone has been paid to do relatively little, has been given opportunities at every turn to game the system and set him for life, and yet his salary could not negate the utter hopelessness felt towards the purposelessness of his job.

Why?

Graeber considers what Eric’s opposite number would do. Put in the same situation, a middle- or upper-class person from a professional background would probably play along, thinking the job was just a stepping stone to bigger and better things, just another feather in the cap of the CV. Being from a working-class family and the first to attend University, Eric was not taught to think and act like this.

Even so, a change in attitude doesn’t negate the falseness of the job. Graeber gives the example of Brendan, a student doing odd cleaning jobs for his college to reduce the amount of student debt he has to pay back. His coworker sums it up better than I could: “Half of this job is making things look clean, and the other half is looking busy.”

You can probably guess the rest: cleaning and tidying things that were already clean and tidied. Brendan estimated the total work needed to be done took five minutes out of every thirty. Nonetheless, he and his coworkers were pressured by their supervisors to appear busy at all times. If the job description was just honest, and admitted there wasn’t much work involved, Brendan and his coworkers wouldn’t have to spend so much time and energy on redundant tasks just to look busy.

Universities are second to the workplace in their obsession on performance. But this isn’t even about performance, or being ‘productive,’ or ‘efficient.’ Brendan theorises that these make-work jobs, when paired with student debt, are supposed to teach students something about playing along with a bullshit job. Graeber takes a stab at what’s being taught here:

David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-graeber-bullshit-jobs#toc20)

- how to operate under others’ direct supervision:

- how to pretend to work even when nothing needs to done;

- that one is not paid money to do things, however useful or important, that one actually enjoys;

- that one is paid money to do things that are in no way useful or important and that one does not enjoy; and;

- that at least in jobs requiring interaction with the public, even when one is being paid to carry out tasks one does not enjoy, one also has to pretend to be enjoying it.

Either people like Eric aren’t prepared enough for our contemporary workplace, or we’ve gotten something terribly wrong about what motivates human beings. That we assume Eric ought to be happy working an effortless job for a hearty salary is to take an economist’s view of things. The economic man, as theory goes, should strive to minimise all efforts and maximise all benefits – “give a lazy person a difficult task, and they’ll find the easiest way of doing it.”

Economists know that humans are not so selfish and calculating, yet this theory they try to apply to all elements of life assumes that we are. It’s the same theory that once brought an all-male team of Neiman Marcus economists together to answer the question, “If I was a Mum, how would I use a computer?” The answer? Mums would store recipes:

https://brologue.net/2023/11/05/fantasy-for-mums/

https://www.wired.com/2012/11/kitchen-computer/

It’s the sort of thinking that aligns with realist mythologies about benefits and compelling people to co-operate:

People have to be compelled to work; if the poor are to be given relief so they don’t actually starve, it has to be delivered in the most humiliating and onerous ways possible… The underlying assumption is that if humans are offered the option to be parasites, of course they’ll take it.

David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-graeber-bullshit-jobs#toc21)

In fact, almost every bit of available evidence indicates that this is not the case.

Take any commons area. Your work’s kitchenette; an open space in a library or school; a public toilet; a community allotment. These are spaces where we might expect people at their most altruistic on the assumption that they’re not the first nor last people to use that space.

Yet researchers continue to be inveigled by a particular story claiming that commons areas are inevitably doomed to tragedy – that a shared resource will always be spoiled by individuals who reason that, if they don’t ruin it first, someone else will, so they might as well ruin it first. You certainly don’t need to be an economist to have experienced this for yourself. Not only is it simple, it just feels right.

The story I’m referring to, of course, is Garrett Hardin’s 1968 Science article, The Tragedy of the Commons. It doesn’t just stop at public places: Hardin scaled his theories up and compared wealthy nation states to lifeboats unable to accept more passengers without sinking. As per this essay in Aeon by Michelle Nijhuis, it’s still taught in environmental science courses – and if you’re into British politics, perhaps the Conservative government’s ‘Stop the Boats’ campaign has sprung to mind:

https://aeon.co/essays/the-tragedy-of-the-commons-is-a-false-and-dangerous-myth

Hardin never actually went out and studied commons areas, you know, like a proper researcher would. Elinor Ostrom did, and found plenty of examples that had persisted for hundreds of years, and never experienced this ‘inevitable’ tragedy that Hardin foretold. It’s not that, in these societies, always co-operating was the norm. Nor was it that avoiding tragedy was guaranteed. Rather, she dispelled the myth of inevitable tragedy by codifying the principles that successful commons shared:

https://ourcommons.org/think/elinor-ostroms-8-principles-for-managing-a-commons/

Now, consider prisons:

Even in those prisons where inmates are provided free food and shelter and are not actually required to work, denying them the right to press shirts in the prison laundry, clean latrines in the prison gym, or package computers for Microsoft in the prison workshop is used as a form of punishment.

David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-graeber-bullshit-jobs#toc21)

We might consider prisons to be the complete opposite of commons areas and assume that they’re full of the least altruistic people one could hope to find. Yet even when inmates work for free, it’s been observed that they prefer to work over, say, watching TV all day, as they might be free to do.

In commons or in prisons, people want to work and feel like their labour is useful and puts something back into society. Bullshit jobs lack this element, and no matter how highly they pay, the salary will never fill the emptiness. It might just be the case that in framing our predicament from the economist’s POV, even in those domains of life that are clearly within the domain of economics, we’ve got it wrong.

We take pleasure at being the cause of something. It’s as intuitive to our development as eating and sleeping. In 1901, German psychologist Karl Groos observed the happiness expressed by babies when they discover they can cause predictable effects in their environment for the first time. He found that it didn’t matter what that effect was, the babies did it for the sake of doing it. Regardless if that action produced some benefit to the baby, they did it to take pleasure at being the cause.

He theorised that this discovery is what sparks our desire to play, and thus what makes us so passionate about games. Who wins or loses doesn’t matter outside of the game itself, and this allows us not only to practice the pleasure at being the cause of something, but to practice exercising this over other humans in a safe environment.

Groos’ observations clearly run contrary to the homo economicus model, which assumes we seek power because of some inherent, primordial desire for conquest, or control over finite resources that guarantee our safety and survival – “If I don’t get to it first, someone else will, so I might as well get to it first.”

Work, then, is a kind of structured play. If our work is useful and puts something back into the world, we are allowed to experience the pleasure at being the cause. If, instead, we find ourselves in a bullshit job, one so pointless that we spend more time pretending to justify it than actually doing it, we are deprived the pleasure at being the cause. Being employed by someone to work a bullshit job is to be forced to pretend to work for the sake of working. It’s an abstract kind of hell.

If make-believe play is the purest expression of human freedom, make-believe work imposed by others is the purest expression of lack of freedom.

David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-graeber-bullshit-jobs#toc21 & https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-graeber-bullshit-jobs#toc28)

Just as a prisoner in solitary confinement inevitably begins to experience brain damage, the worker deprived of any sense of purpose often experiences mental and physical atrophy.

A human being unable to have a meaningful impact on the world ceases to exist.

Part II: Keep Your Shirt On

David Graeber was an anarchist. He was disposed to being a gadfly, coaxing out difficult, morally troubling questions that not only make sense, but demand answers that make sense, too. He wasn’t a hacker, but there’s something about the impact of his work – not just Bullshit Jobs – that makes me want to compare it to the 1996 Phrack article that all hackers read as a rite of passage: Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit:

http://www.phrack.org/issues/49/14.html#article

Smashing the Stack wasn’t an outright discovery of buffer overflow exploits, but it definitely raised the consciousness of readers back in the day. What lay as a dormant flaw in many a computer program was suddenly summoned forth in this article, at which point the number of hackers who had the knowledge to exploit these flaws began to grow. Once Smashing the Stack was written, you couldn’t unwrite it. Neither can we unwrite Bullshit Jobs.

When Graeber wrote On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs in 2013, he brought forth dormant ideas we express in our dissatisfying world of work:

It’s as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working. And here, precisely, lies the mystery. In capitalism, this is precisely what is not supposed to happen.

David Graeber, On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs

In Bullshit Jobs, there’s no intellectual corner he won’t turn to in developing his theory – philosophy, history, economics, sociology, politics, and so on. If we’re going to talk about work as a kind of structured play, and the power dynamics between the boss and their workers, only one field of study is confident enough to get right under your nails, and yank at that thing that ought to be said, where others daren’t say.

Only a psychoanalyst could suggest in earnest that the boss-worker dynamic is a nonsexual, nonconsensual BDSM relationship.

In Chapter 4, Graeber recalls an email thread with another respondent, Annie. She described how she went from working in childcare to “a medical care cost management firm” making a living wage. Basically, the firm existed as a plaster on America’s haemophilic healthcare system. She was provided no prior training, and her role was effectively to take some forms (paper or digital, I’m not sure), highlight some fields, and return them to their place for someone else to do something with them.

The company culture, as she described, was “one of the most abusive environments I ever worked in,” emphasising in parenthesis that talking to coworkers was forbidden. But the real kicker came when, after making a highlighting error consistently for two weeks, pulled aside by her manager, and shown how to correct the mistake, she would continue to be pulled aside, time and time again whenever someone came across one of the mis-highlighted forms.

She was shown how to correct her mistake. That’s not something a manager would simply forget. Yet she pulled Annie aside to talk about it every single time. It’s as if she was exercising her arbitrary power over Annie for the sake of it.

Lynn Chancer, a sociologist, combined the psychoanalytic theories of Erich Fromm and Jessica Benjamin to write Sadomasochism in Everyday Life. Here’s the quick rundown: in a sexual, consensual BDSM relationship, partners are aware they’re playing a game. That’s part of the contract. The bottom struggles to gratify the top who will never meet the bottom’s need; likewise, the top endeavours to persistently exert dominance over the bottom that, outside of the game, is purely fantasy.

The top experiences pleasure at being the cause; the bottom, though subjugated to the top’s power, also takes pleasure at being the cause by invoking a safe word. In one word, the bottom has the power to willfully change the top from a tyrannical inquisitor back to their loving, caring partner.

In real-life sadomasochistic relationships, there is no safe word. You may say, “I quit,” but this isn’t a safe word de jure. If you quit your job, the work relationship ends. That’s like saying the safe word to your partner, breaking up with them immediately, and turning them out of doors. Naked. Poor, forked radish.

David Graeber spends a scorching minute talking about psychoanalytic theories of power and BDSM, yet encapsulates it all in seconds with this gem:

“You can’t say “orange” to your boss.”

Part III: An Awful Bit of Kit

I hope you’ve brushed up on your Dave Gorman. It’d help if you’ve at least watched the first episode of Modern Life is Goodish. Not that it matters, mind you…

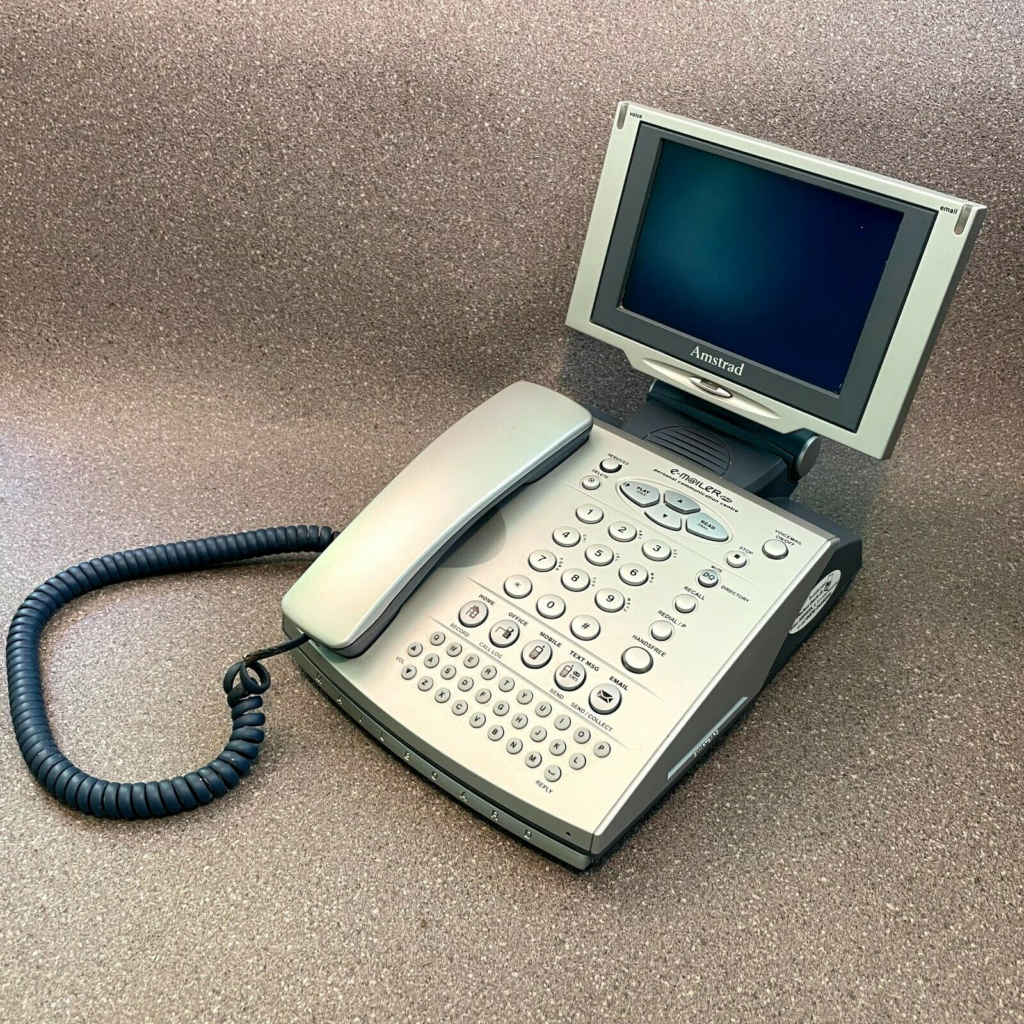

Presenting: Lord Sugar’s Amstrad Emailer:

Christ, what an eyesore. You know how Blackberries were all the rage for a hot minute with their QWERTY keyboards, and then the iPhone vaporised them with touchscreen keyboards? This is like a proto-proto iPhone.

The Amstrad emailer looks like an engineering student’s failed attempt to make the iPhone, like they’ve just jerry-rigged all the necessary functions together and went, “It’s all there, hopefully you can see the concept behind it. You want to play hangman? There’s an app for that.” It’s a failed iPhone attempt from the year 2000 that looks like what people in the 60s thought technology would look like. It’s an anachronism whichever way you look at it.

The Emailer was enshittified from the start. It was never not a failure. Every generation sold at a loss – to claw back the money lost, the device ran on a pay-as-you-use business model. Wanted to video call someone on your E3? 50p, please:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/3658722.stm

Wanted to play some old ZX Spectrum games that’d been discontinued over ten years prior? It’s pay to play, son, just like the arcade days!

Emails? Updated automatically every morning – 15p, mes amis.

Oh, and you’re not going to believe this – it had ads for screensavers that you could remove by paying a one-time fee of £15:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/AMSEmailer/posts/368063270673395

Lord Sugar genuinely believed – as all hype merchants do when their supply goes supernova and begins to crystallise – that the Emailer was the way. iPods? By Christmas 2006, “Dead, finished, gone, kaput:”

Amstrad’s own CEO, meanwhile, wasn’t so hot when sales started nosediving in proportion to Lord Sugar’s raving:

https://www.theregister.com/2001/10/02/amstrad_ceo_resigns_over_sir/

Of course, in the interest of balance, here’s the BBC’s take:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/1574900.stm

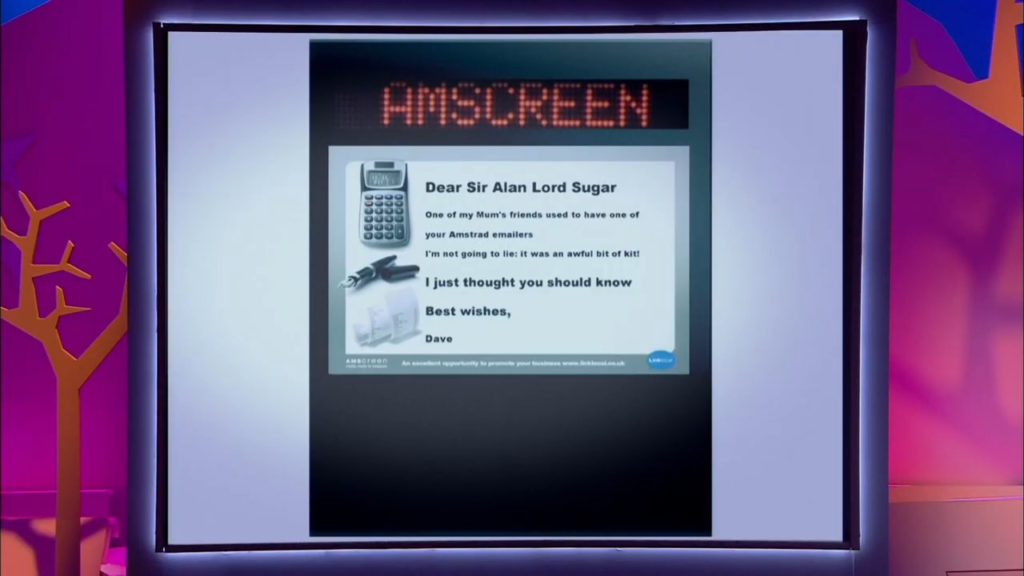

While Lord Sugar had sold off what was left of Amstrad after the failure of the Emailer, he was (and still is) the chairman of Amscreen. We’ve all passed at least one electronic sign in the UK, and chances are it was manufactured by them. Gorman’s trawl through the AMS cinematic universe led him to a marketing stunt for the Amscreen. A story had made rounds claiming a woman had rented one at a petrol station for £100/month to break up with her boyfriend. The key word here is “£100/month.”

Keep in mind that this was still a time where corporate advertising was still in its “How do you do, fellow kids?” stage of trying to appeal to the internet audience. Both Lord Sugar and his son (“Simon, the oldest of Alan’s sugar lumps”) tweeted about the stunt. You too could rent a screen for as little as £100/month at this link…

https://web.archive.org/web/20130215192337/http://www.linklocal.co.uk/

This was also a time where posts on Twitter that ‘did numbers’ were rare specimens. Twitter in 2013 is to Twitter in 2020 what Twitter in 2020 is to X in 2023. Getting Lord Sugar’s attention on Twitter could be easy, but it wouldn’t have much reach.

Gorman could do much better. He had Chekhov’s Billboard on his side: If in Act I you let people rent ad-space at cheap rates and with few restrictions, then someone by Act III is going to rent that space to take the piss out of you.

That was, until someone from Amscreen’s customer support emailed him saying his proposed ad had been rejected. But this rejection only serves as a corollary to his theory:

I think we are conditioned to not look at the details. Life is constantly telling us we don’t have to look closely. In fact, authority often tells us not to look.

Dave Gorman, Modern Life is Goodish (Series 1, Episode 1)

Why? Well, as a hacker (ahem – adversarial interoperator), it’s not that businesses are opposed to the likes of us looking, so long as it’s the right people.

A white-hat pentester may be paid to figure out how something works, and how it fails. The business establishes the rules of engagement to which both parties consent. The pentester has to break in as if they were a real threat. So long as they tell no tales, they maintain an appearance that the company’s products are secured from some threat. Keeping up appearances is important, because most advertising focuses exclusively on how well a product works, as opposed to how well it fails.

On the flipside, when a tinkerer engages in some adversarial interop, it’s a different story. They are trespassers on intellectual property. Despite the fact that the tinkerer has proven that a product can be improved, businesses will often smear their attempts, pulling the curtain back, trying to get us not to look any further. “We take the security of our users seriously,” they’ll say, but without the audits and CVEs to prove the tinkerer’s third-party solution as being insecure.

What I’m saying is, Dave Gorman was doing a bit of hacking. Yes, maybe clause 6 of the Ts&Cs meant they reserved the right to refuse an ad for any reason, but still, who seriously thought someone was going to use an Amscreen to tell Lord Sugar himself the Emailer was ‘an awful bit of kit?’

https://web.archive.org/web/20120920055242/http://www.linklocal.co.uk/terms_and_conditions.html

Yes, the Amscreen plan fell through, but therein lies Gorman’s point: We owe it to ourselves to look and ask questions where we’re not supposed to. We didn’t read stuff like Ts&Cs back then, and we certainly don’t read ’em now. But we should.3

At the end of the show, Gorman shows his alternative to the Amscreen: he asked one of his mates to stick the message on the side of his van, and drive it to Lord Sugar’s local petrol station. In the second series, a year later, Gorman and his mate drive the same truck into one of Lord Sugar’s restaurants. They eventually replaced the message with a picture of Sugar’s face and the caption, “yum yum!”

Then they drove the van to a dogging site. Sorry, but you’ll have to look that one up yourself.

Part IV: Saying “Orange”

So, about my Dave Gorman idea.

It’s something that I (probably) shouldn’t have done, and it’s something you shouldn’t try at home. Granted, it wasn’t some great heist like when Oobah Butler smuggled rebottled courier piss to the #1 spot on Amazon:

https://www.channel4.com/programmes/the-great-amazon-heist

But Dave Gorman and Oobah Butler are Professional Comedians™/Pranksters™. They’ve got teams of people handling the legal stuff. I’m just some guy.

“You can’t say orange to your boss” is such a great phrase on its own. You either get it, or you don’t. That’s what prompted me to set about putting it on a T-shirt. I wanted to start small, just to see if I could do it. I don’t put things on T-shirts often, you know? So, I began to google…

The site I settled on let me preview my design. I didn’t need anything fancy: just the words “You can’t say ” ORANGE” to your boss” in orange Arial on a black shirt. But the website didn’t like me using the word “boss” in my design. In fact, the banner claimed it was against their Community Standards:

I blinked, unperturbed. I couldn’t even say “orange” to this website, but I knew why. It’s a catastrophe waiting to happen – you can’t just let anyone order shirts brandishing threats like “BE GAY, DO CRIMES, K*LL YOUR BOSS” en masse! And yet, what if you wanted to make your own custom design for your #1 boss, because they’re genuinely a standup person? Tough luck – to secure against a PR flub, someone decided to filter ‘boss’ entirely, because folks who aren’t bosses are so easily inflamed.

If I know anything about input sanitisation, it’s that covering all bases is critical. If you’re trying to protect against SQL injection, you might filter out or change special characters to sterilise embedded queries that might be read by the database software. This filter needs to get it right every time. An attacker only needs to get it right once – they can fuzz their query, generating different permutations of the same attack, in the hopes that one permutation slips through.

The word filter might stop me from using “boss,” but what about “boss?”

No, you didn’t read that wrong – I’ve inserted an invisible Unicode character in between “Bo” and “ss”. Phishing scams often do similar4, registering domains that look authentic, but use lookalike characters from other language scripts. Here’s an O:

O

And here’s an omicron:

Ο

Convincing, ain’t it?

The shirt having been ordered, a ‘no’ having been bent back to a ‘yes,’ another thought occurred to me. Did the website deny me saying “orange” to my boss because I was a guest user? Had there been previous designs using the word ‘boss’ that had been accepted on the website? I had to root around.

Yes, yes there was. The chicanery ran deeper:

A guest user can’t say orange to their boss without a workaround (one that’s easily fixed). Registered users, meanwhile, are able to make a design calling their boss a twat (doing some gig work, presumably), and that’s all above board.

In the final purchase, whether I have an account or not should be irrelevant – I’m still giving them my name, address, card details, and I still get badgered by emails I didn’t ask for and opted out of. An account should just make the checkout process faster.

For this business to deny guest users arbitrary privileges, there must be some value they can extract from my creating an account. One of the clauses in its privacy policy states that if I were to create an account and used it to store my address, Google Maps Autocomplete would be used to verify it. If I wanted to sell on the website, Google Fonts and Calendar would get involved as well; on the business’s behalf, Google Analytics processes user data to evaluate one’s activities on the website.

Google is essentially an intermediary between me, the customer, and the website. The idea is that the website promises it can better tailor my experience if I sign up. Google, like all ad-tech companies, promises the business untold riches. The Algorithm’s™ secret sauce will, like cordyceps taking over its victim’s nervous system, order me to shop, buy, and shop again, able to predict what I want to buy before I even think about it.

Google promises me what it promises everyone who uses its services – it’s not going to be evil. I like companies that promise me this in Act I, because by Act III, an investigator’s going to find out that nice ain’t good:

https://geekdom.social/@bigolifacks/111569359710296547

They want me to set up an account, but I would prefer not to. They would like to use ads, trackers, and cookies to tailor my experience. I prefer not to. UBlock to Google: Ah ah ah! You didn’t say the safeword!

Two weeks after ordering, the shirt arrived (Bo not included). You can see my invisible character got turned into an arrow, but it hardly obscures the message, and after a while, you hardly notice it’s there.

If there’s a moral for this story, it’s this: When an individual or group in power tells you ‘no,’ tells you not to look, tells you to not think about it so much, that’s when we should look closer. We might just find a way to bend that ‘no’ back into a ‘yes.’

We might just find a way to say “orange” to our boss.

- I refer strictly to the folks who serve you at the ticket kiosk, prepare your food at the counter, and clean all the capital-S Shit™ left lying around at the end of the film. Sometimes all in the same day. Besides having to carry your Shit™ to your seat, in most cinemas you are lifted and laid by staff. It’s perhaps caring labour taken to an agonising extreme. At least if you’re a nurse, you’re tending to the sick and dying. If you’re working in public transport, at least you’re helping people to comfortably get from one place to another. If you’re working in a cinema, often you are the reception staff, food vendor, concierge, janitor, and much more. Sisyphus should be so lucky – he gets to roll a boulder up a hill for all eternity. ↩︎

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Amstrad_E-mailer_Plus.png ↩︎

- Technical specifications – standards – though boring and dry, are worth a read. If you’ve ever wondered how one bit of technology works with another bit of technology, there’s a standard for it. ↩︎

- (While I’ve drawn your attention, can I just point out that, as a security fellow, I sympathise with journalists who are pressed to use different words to describe the same kind of scam. Look, phishing’s phishing, regardless of what device it happens on. DM me on Mastodon if you’re being forced to use ‘vishing’ or ‘smishing’ against your will. ↩︎