- Content warning: Both of these books explore weight stigma, wellness culture, and fads that can be extremely destructive, physically and mentally. If you’re made uncomfortable by that, give this post a pass.

- On the flipside – if I get it wrong, I hope I’ve got it wrong better than most.

EDIT 12/12/23: I am urged to point out that, although most fad diets and endeavours to regulate caloric intake are swindles, Harrison points out that there are cases where one’s body legitimately requires a specific diet. For example, those with celiac disease are advised to avoid foods with gluten, as their immune system treats gluten as an active threat and will attack bodily tissues. This, in turn, damages the small intestine, and impairs nutrient intake:

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coeliac-disease/

Health and ‘wellness,’ in my lifetime, has always been treated as a virtue, and it’s the ethical and moral responsibility of the individual to be in good shape and health – anything less, and there’s something wrong with you, and doubly so if you’re female. The solution to achieving a ‘normal’ weight that everyone can use? Regulate your food intake with a diet. It’s not hard – reduce your food intake, swear off ‘bad’ foods, or chase the latest diet, and don’t think about other health outcomes.

This sort of thing falls in line with what Christy Harrison, professional anti-diet dietitian, calls ‘diet culture’ – a product of the medical paradigm that shapes our world today. She spends the first half of Anti-Diet deconstructing the bullshit of diet culture through materialistic analysis. For most of pre-industrial history, having a larger body was seen invariably as a sign of status, or a benign part of aging. Even during the peak of industrial capitalism, Victorian actresses who were big-bodied were more desirable.

As we began to move from feudal societies to merchant capitalism, and then industrial capitalism, health also saw a paradigmatic shift, from humourism to the mechanistic view of mind and body, popularised by René Descartes. Fast-forward to the aftermath of the French Revolution, and you’ve got intellectuals like Francis Galton and Adolphe Quetelet popping up all over the place who were obsessed with this idea of ‘normality,’ and how we might take statistical measures to find the most ‘normal’ man of any given country.

Of course, in Quetelet’s day, ‘any given country’ meant Europe, and its predominantly white population. He developed BMI as an adaptation of his work in astronomy, trying to predict the movements of the planets and stars. It was never intended as a predictive measurement of health outcomes.

Normality wasn’t just average – it was considered a kind of perfection that every person ought to strive for. Any deviation to this was considered by Quetelet as a ‘monstrosity.’

One industrial revolution brought clothing production at scale; one world war taught everyone how to ration; and one ad campaign featuring made-up women and slender waistlines that espoused ‘peak femininity’ put an end to that. Thin was in, and if women didn’t want to be like the Gibson Girls, well, they didn’t have much of a choice.

Thing is, every single diet you could try under the sun is a swindle in the end. If you don’t waste your money buying exotic foods, supplements and fancy gadgets you might not even be able to afford on the regular, you rob yourself of time through painstakingly planning meals and counting calories. You reinforce the belief that weight gets the only say in your overall health – in the end, alienating yourself from food in pursuit of a ‘normal’ waistline isolates you from the culture of food itself, dodging social events to keep score. Ultimately, you rob yourself of your right to happiness.

That’s the swindle – the material force of wellness culture manipulates you into second-guessing yourself, your identity, and then the industry that’s built around it can sell it back to you at a premium, in the form of programs, rules, protocols, and a promise that being thin will make you accepted.

The second half of Anti-Diet discusses how we might go from jam tomorrow to jam today. Particular attention is given to the intuitive eating approach developed by fellow dietitians Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch. They go back to basics – we were born to eat, and the body gives our mind clear signals when it wants to eat, and we should listen to those signals.

This is, among other points, what separates intuitive eating from just being “a diet by another name.” There are no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ foods – only what you need to refresh and nourish you. Have an apple, or a burger, there’s no shame in it.

I’m far from qualified to give an expert opinion on intuitive eating. I do, however, think that characterising the inner voices we have whenever we go to eat something is useful. Tribole and Resch, in their work, establish a taxonomy of voices that we can use to ‘challenge the food police.’ I particularly like the classification of the Food Anthropologist – neutral, introspective thoughts that don’t judge what you’re eating, and so it’s not a voice created from external pressures.

There’s a lot of areas of life, I think, that anthropology ought to be more discussed in the everyday. Studying history’s one thing, but combine that with studying our behaviour, cultures, biology, languages, and societies, and we might just find the answer to what it’s really all about, when we get right down to it. Anthropology shows us the rules are made up and the points don’t matter.

In Wellness Trap, Harrison takes a deeper dive into the history of wellness, and the phenomena that have come about because of it. This not only means exploring weight stigma again, but also social determinants of health, conspiracy theories, and alternative medicine, and how they all relate.

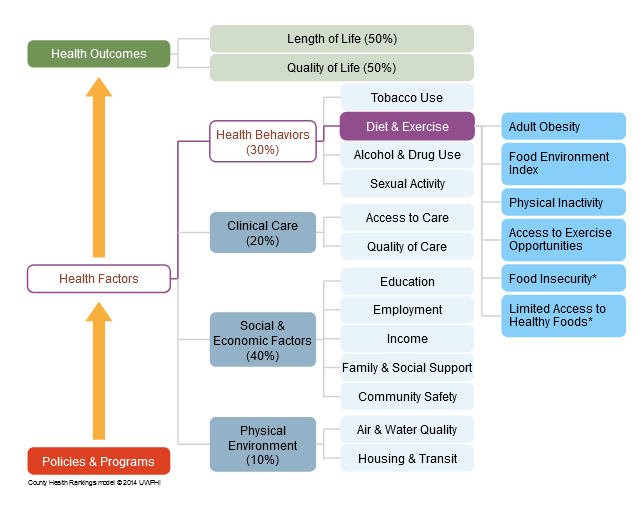

Solutions to weight problems are often touted as ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches, and that couldn’t be further from the truth. Every body’s different, and weight, contrary to popular belief, does not have the final say in your overall health. Social determinants, and not individual traits, have a much more significant say:

The diagram the UK government’s website gives is kind of shite – one of Harrison’s sources, over in the States, gives a clearer picture:

https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/county-health-rankings-model

Seventy percent of one’s health outcomes are associated with socioeconomic factors. The one factor we fret over isn’t nearly so important, in the grand scheme of things. The other factors are phenomenally more important – yet, while most I think would agree that they’re important, they are not seen and considered important in the context of health enough.

Putting it politely, there’s a lot of mis- and disinformation in the health sphere. Harrison points out an unusual spike in popularity of The Secret1 at the start of the pandemic. It’s a book that posits magical thinking as the panacea to a healthy, successful life. Like attracts like; positive thoughts attract positive actions. What you think about, you bring about.

The Law of Attraction is essentially a form of autonomic mind control. There have been many, many claims to mind control throughout history, and all of these claims have been pure, unadulterated bullshit. Please do tell the single mum of two from Methil, grinding the poverty line and economising to pay rent during our country’s omnishambles, that she just has to ‘let nothing else but wealth exist in [her] mind.’ Call me deranged, but I don’t think it’s her fault that her government doesn’t want to spend money on policy initiatives and programs that might just mean she can have nice things.

Then there’s the hordes of conspiracies, chief among them the antivax rabbit hole. Harrison mentions an article put out by the US’s Center for Counting Digital Hate (CCDH), which identified twelve social media influencers as the source of the majority of vaccine misinformation spread online:

https://counterhate.com/research/the-disinformation-dozen/

COVID fed into conspiracies a great deal due to it being a period of what Harrison calls ‘epistemic anxiety.’ No-one knew when we’d have a cure, no-one knew when we’d be able to go out again, and so on. Society was under siege from an invisible threat which we had no answer for, so everyone started scrambling for their own answers.

Those who believe in conspiracies aren’t stupid – their hearts are in the right place, but often for more fantastical reasons than reality can provide, as I often like to quote from Cory Doctorow:

https://locusmag.com/2023/05/commentary-cory-doctorow-the-swivel-eyed-loons-have-a-point/

Big Pharma makes money from the sale of vaccines and medicines that it has the patents to. They’re not manufacturing pathogens themselves. It’s not absolutely loony to suggest, for example, that Big Pharma companies have something to gain from selling weight-loss drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy. There are actual conspiracies of substance, as RationalWiki documents:

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Big_Pharma#Actual_problems

When the US’s National Institutes of Health released a report in 1998 to thumb the BMI scales and hurl millions of Americans from the “overweight” category to “obese” overnight, the country suddenly found itself in medias res of an “obesity epidemic.” Except there was no flashback scene, no exposition monologue; there wasn’t so much as a freeze frame, cheesy record scratch sound effect, moog synth belting out the opening hook to Baba O’Riley, and a guy wondering how we got here.

That report was based on another written piece by an organisation calling itself the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF, since renamed the World Obesity Federation). Turns out that said organisation was being bankrolled by two drug companies, Hoffmann-La Roche and Abbott Laborities. One, at the time, owned the patent for orlistal, sold under the brand name Xenical, and the other manufactured sibutramine hydrochloride, sold under the brand name Reductil:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1479667/

That ought to raise an eyebrow, at least. There’s a difference between that, and madcap kooky-koo ideas like vaccines causing autism, the earth being flat2, powerful people are lizards, face masks don’t stop viral spread, fifteen minute cities will mandate ‘climate lockdowns,’ and on and on and on.

Rather than debunk existing conspiracies head-on, it may be better to prevent the rooting of new ones in the future by prebunking disinformation before it gets out of hand:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/misinformation-desk/202108/what-is-prebunking

At the same time, blindly trusting in science makes us more likely to believe and repeat pseudoscience. Trying to check the veracity of a source feels like we have to do deep dives all the time – it takes much more effort to refute bullshit than to create it. Rather than do a deep dive, we could instead try to observe SIFT: Stop, Investigate Source, Find Better Coverage, Trace Back to Original Context.

https://guides.lib.wayne.edu/sift/intro

To this end – although this is beyond the scope of the book – news aggregate websites like Ground News are an essential tool for investigating news sources and finding better coverage:

Challenging the way things are – the way things are because ‘it’s the way it’s always been’ – means we’ve got to put the Journalist hat on, to sift and prebunk, if we’re to get anywhere. Thanks to the Web, among other factors, we’re the most educated generation in human history. That also means there’s never been a worse time to pull slack and assume everything will eventually make sense.

It need not be a Sisyphean task. Be it diet culture, weight stigma, conspiracy theories, the point at which we are most assured – comfortably confident that there is no alternative, this is how things are – is the point at which we must reflect critically upon our beliefs the most. Anti-Diet and The Wellness Trap intercept at such points.

Both Anti-Diet and The Wellness Trap are available at retailers via Harrison’s website:

https://christyharrison.com/book-anti-diet-intuitive-eating-christy-harrison/#order

https://christyharrison.com/the-wellness-trap/#order

- We have a copy of The Secret in our house that I only learned about last year. How it got onto my shelf, I have no clue. My best guess is that without knowing anything about the author, the front cover kind of gives the impression of a sexy murder mystery thriller novel. It looks like the kind of book you’d buy in an airport WHSmith. Maybe I can manifest a private jet so I never have to encounter it again… ↩︎

- Flat-earthers ought to ditch the tinfoil hats and take up reading Discworld, where the world is, quite famously, flat. Also on Discworld, the notion that the Disc is spherical is deep-rooted in Omnian dogma. Not everyone’s convinced everything they know stands atop four elephants who are themselves riding a star-sized turtle through space. The turtle moves anyway, because by the time it’s had another thought, they’ll have all shoved off. ↩︎